|

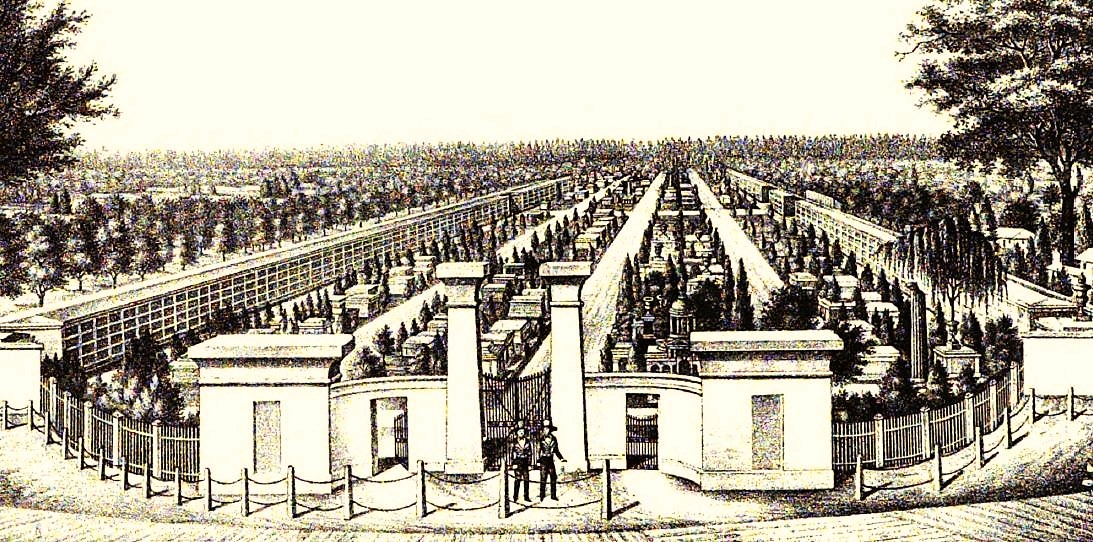

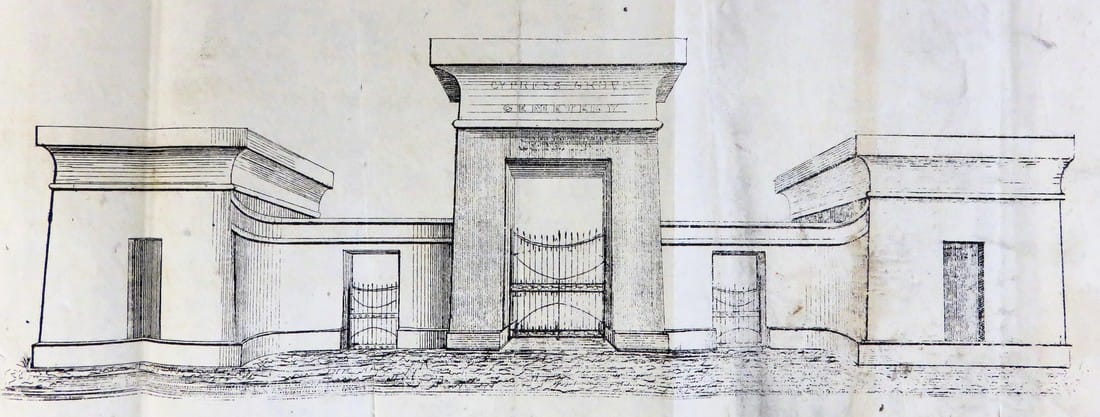

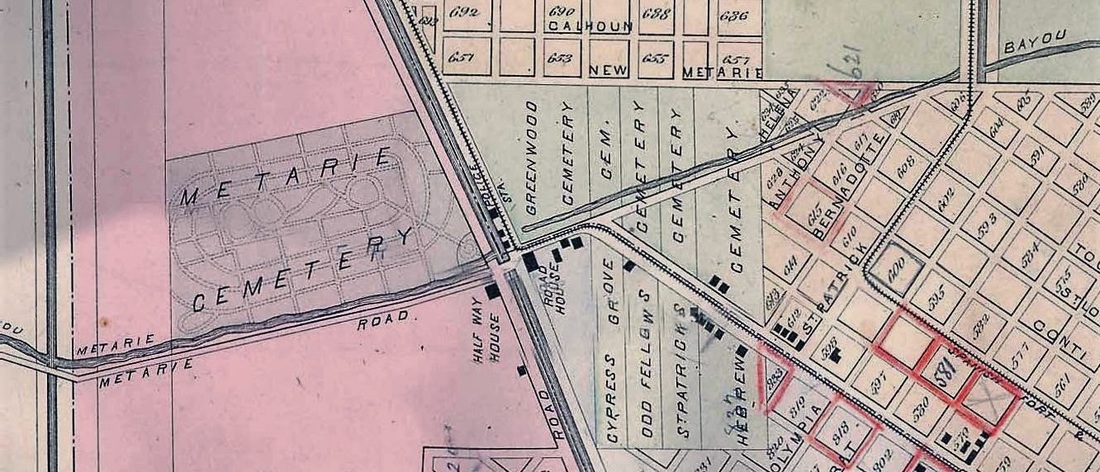

Part One of Two in an examination of historic architectural landscapes at Cypress Grove Cemetery. The foot of Canal Street at City Park Avenue is surrounded by cemeteries. At one end, the bronze statue of the Elks Lodge tumulus presides over ever-bustling traffic - right now, in December, the Elk has been decorated with a festive red nose. Facing the intersection from another side is the tall edifice of Odd Fellows Rest. The entrance gate of Cypress Grove stands out even in the grandiose company of these monuments. Comprised of two gatehouses and towering Egyptian Revival pillars, the gate has stood longer than the Elk, the Odd Fellows, or any other cemetery in the area. Within these gates is the oldest rural cemetery in New Orleans. Cypress Grove’s significance is self-evident – its wide avenues showcase example after example of high funeral architecture, of stories that strike the heart of the New Orleans history. But there’s another story among the thousands of tombs in the cemetery. It’s the story of a landscape now obscured by time, of what it used to mean to walk through these aisles. Beyond the mowed grass and paved paths is evidence of what once was a lush, tree-lined landscape on par with the garden cemeteries of the northeast. If you look hard, you can still find it there. The Firemen’s Cemetery Cypress Grove was founded in 1840 by the Firemen’s Charitable Association (FCA), now known as the Firemen’s Charitable Benevolent Association (FCBA). The Association was organized in 1834, about five years after the first New Orleans volunteer fire companies formed. Originally, the Association served in a manner similar to other mutual aid societies: providing social and financial support to the city’s volunteer firemen. Within its first decades, however, the Association became the fire department itself. Until the city switched to a paid fire department in 1892, the Association was responsible for all firefighters in New Orleans – and all firefighters were volunteers.[1] The tale of the founding of Cypress Grove is one well-known to cemetery lovers in New Orleans. On New Year’s Day 1837 while carrying out his duty with Mississippi Fire Company No. 2, thirty-five year-old Irad Ferry perished in a fire on Camp Street. Dubbed the “the first martyr” of the newly-formed fire department, Ferry was venerated with a public funeral and a large memorial march. He was originally laid to rest in Girod Street Cemetery. Along with relief services for their members, benevolent societies of this time provided burial benefits to their members. The Firemen’s Charitable Association was no different, and considered purchasing a section of Girod Street Cemetery for that purpose with plans for Ferry’s monument to be built at its center. But in 1838 the death of Destrehan plantation owner Stephen Henderson widened the Association's prospects. In addition to multiple provisions regarding people enslaved by Henderson, the will specified large bequeaths to religious and social charities, and $500 per annum to the Firemen’s Charitable Association.[2] On Sunday, April 25, 1840, a nearly one thousand firemen, clergy, and prominent citizens marched through downtown New Orleans, each wearing mourning bands and a few carrying urns representing the ashes of their martyred comrades. At Canal Street, they boarded train cars and traveled to Cypress Grove Cemetery, where they re-interred the remains of Irad Ferry beneath a great monument designed by J.N.B. de Pouilly and constructed by stonecutter Newton Richards. In a nearby tomb constructed for this purpose, the remains of eleven additional firemen were buried.[3] The Rural Cemetery At its founding in 1840, Cypress Grove became the sixth active cemetery in New Orleans, and the only cemetery at the lake-side foot of Canal Street.[4] Its predecessors were decidedly urban in design: dense, utilitarian though beautiful, and without significant landscaping. A possible exception to this rule was Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, located in what would become the Garden District. Lafayette No. 1 has been referred to as a “transition” cemetery between urban and rural model cemeteries. But even this cemetery was squeezed into a single city block, with no room for the rolling greenery that had become popular in American cemetery design by 1840.[5] Cypress Grove was destined to become something different. Enormous in land area by contemporary New Orleans standards, it was conceived by relative newcomers to the New Orleans Francophile aesthetic. Members of the FCA were often northern-born – for example, Irad Ferry was from Connecticut – and thus influenced by English sensibilities. The Americans brought with them new ideas for cemeteries. They were inspired by what they saw at Mount Auburn Cemetery in Massachusetts, Laurel Hill Cemetery in Philadelphia, Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, and many more. These were cemeteries that were designed instead of planned, with undulating pathways that strolled past weeping willows and reflecting pools. This was the rural cemetery movement, a great shift in the history of cemeteries that would change the American perception of death forever. The rural cemetery movement arose in the northeastern United States as a result of the expansion of cities. Advances in industrialization within the urban landscape created in city-dwellers a longing for the countryside. Furthermore, this same industrialization advanced the American middle class in such a way that recreation was newly defined. Inspired by English landscape design, the rural cemetery was the predecessor to the public park – in fact, Central Park landscape architect Frederick Law Olmstead designed one such cemetery in California. This shift in the appearance and purpose of cemeteries coincided with many American cultural movements like Romanticism and the “beautification of death period.” The Firemen’s Charitable Association was certainly aware of this trend. In addition to the explicit use of the term “rural cemetery” in FCA planning documents, the Association expressed a disdain for contrasting urban cemeteries: It would seem almost superfluous to set for the advantages of this rural cemetery. The rapid growth of our city has already encroached upon the tombs of its fathers, and the sacred relics of the dead have been compelled to give way to the cold and selfish policy of speculators, and the intrusion of business; and the solemnity of the grave yard is disturbed by discordant shouts of merriment, and the baleful proximity of the dissolute.[6] If there was any question as to whether the FCA was directly influenced by the rural cemetery movement, one must note that the iconic Cypress Grove entrance gate is a near-exact facsimile of the gate at Mount Auburn. The Cemetery at the Half-Way House For those in FCA who wished Cypress Grove to be a truly rural cemetery, a better location could not have been chosen. The new cemetery was situated at the confluence of vital infrastructure lines: the New Basin Canal and Shell Road, Bayou Metairie, and rail lines at Canal Street. Although the area was an important checkpoint in travel through the area, it was largely undeveloped. One map from 1849 describes the area as a “ridge covered with live oak, persimmon, liriodendron, pecan, wild cherry, interspersed with acacia trees.” The cemetery itself would have, in its own way, water features much like the rural cemeteries it emulated. Early descriptions of the cemetery plan boast “frontage” on both the New Basin Canal and Bayou Metairie. In fact, Cypress Grove Cemetery once straddled Bayou Metairie (today City Park Avenue). The bayou divided Cypress Grove Cemetery No. 1 (present-day Cypress Grove) and Cypress Grove Cemetery No. 2, a potter’s field now covered by Canal Boulevard. The location of the cemetery not only suited the rural aesthetic but also the new role of the cemetery as a venue for picnics and outings. The Shell Road, which ran alongside the New Basin Canal toward Lake Pontchartrain, was a popular day trip for visitors and locals alike.[7] The Half-Way House and Road House were located at the meeting of the Shell Road and Bayou Metairie – both places of rest, refreshment, and entertainment located at the midway point between the Mississippi River and Lake Pontchartrain, further cementing Cypress Grove’s destiny as a park-like destination. Growth and Change Those who were drawn to own tombs and lots after 1840 chose Cypress Grove for its bucolic location, wide aisles, and landscaping. In its first twenty years, the cemetery would be filled with some of the grandest architecture New Orleans craftsmen could offer. Its aisles, all named after trees and plants, would bristle with their namesakes shading each pathway. The finest cast iron fences would encircle family tombs clad in marble and Pennsylvania brick. Cypress Grove became, in some ways, an extension of Girod Street Cemetery. Protestants and other non-Catholics sought property within its walls, bringing their taste in obelisks and urns with them. Cypress Grove became home to the second tomb for traditional Chinese burials in New Orleans. The Slark and Letchford families built two tombs inspired by stately Gothic spires along the cemetery’s marble-clad side wall vaults. Cypress Grove would not be alone at the confluence of bayou, canal, and railroad for long. In the same year Cypress Grove was founded, St. Patrick’s Cemetery No. 1 was established. Cypress Grove would be joined by Greenwood Cemetery, Odd Fellows Rest, Dispersed of Judah and other Jewish cemeteries, Charity Hospital Cemetery (now Katrina Memorial), and Masonic Cemetery No. 1. In 1872, Metairie Racetrack would be converted to Metairie Cemetery, and Cypress Grove would be supplanted as the great rural cemetery of New Orleans. One hundred seventy-five years after Cypress Grove’s dedication, there are twelve cemeteries clustered near the intersection of Canal Street and City Park Avenue. The New Basin Canal was filled in the 1960s and replaced by the Pontchartrain Expressway. Metairie Bayou has been filled and City Park Avenue widened atop it. The Half-Way House and other former New Basin Canal structures were demolished in recent decades. Today, the New Orleans Emergency Communication District buildings are located at the site. Cypress Grove may not be so easily recognized for what it once was. Its trees are mostly missing, replaced by deep ruts in sod where herbicide has taken hold. Many of its great structures have changed or completely disappeared – tumuli stripped of their grassy knolls, wall vaults stripped of their marble facing. Next blog post, we dive deeper into the architectural history of specific tombs and structures in Cypress Grove Cemetery and how they have changed over time. [1] Thomas O’Connor, ed. History of the Fire Department of New Orleans (New Orleans: FMBA, 1890), 54-57.

[2] Ibid., 65-70; “Mr. Henderson’s Will,” Daily Picayune, March 17, 1838, 1; Although unrelated to Cypress Grove, the will of Stephen Henderson and how it was executed bears some interest. Among other provisions, Henderson attempted to arrange for the gradual emancipation of his many slaves, with the option for some to be sent to Liberia. Find more here, and here. [3] O’Connor, 70-71. [4] St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 and 2, Girod Street Cemetery, and Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. At least two Potter’s Fields or indigent burial grounds and unknown family cemeteries were also in the City. [5] Dell Upton, “The Urban Cemetery and the Urban Community: The Origin of the New Orleans Cemetery,” in Exploring Everyday Landscapes: Perspectives in Vernacular Architecture, ed. Annmarie Adams and Sally McMurry (Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 1997), 131-145. [6] Firemen’s Charitable Association, Report of the Committee of the Firemen’s Charitable Association, on the Cypress Grove Cemetery (New Orleans: McKean, 1840), 4. [7] Visitor’s Guide to New Orleans (New Orleans: J. Curtis Waldo Southern Publishing & Advertising House, Nov. 1875), 30-33.

5 Comments

diane dempsey

12/12/2016 03:44:28 am

very interesting -- thank you

Reply

12/20/2016 07:39:19 pm

I would like more photos showing pre-World War II benches no longer a feature of local cemeteries like the one at the end of this article. Good info in articles.

Reply

Emily Ford

12/21/2016 07:29:22 am

Here's one of Greenwood that I've always been fond of: https://www.loc.gov/item/2015645056/

Reply

Andrew Terrebonne

12/22/2016 08:40:50 pm

No mention of the Leeds cast iron tomb?

Reply

12/17/2018 04:29:47 am

I was very pleased to find this web-site. I wanted to thanks for your time for this wonderful read!! I definitely enjoying every little bit of it and I have you bookmarked to check out new stuff you blog post.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

About the Author:Emily Ford owns and operates Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

- About

-

Restoration

- Services

-

Portfolio

>

- Turning Angel Statue, Natchez, MS

- Ledger Monument, Baton Rouge, LA

- Pyramid Statuary, New Orleans, LA

- Bronze and Granite Monument, Carville, LA

- Box Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Vernacular Concrete Monument, Pensacola, FL

- 1830s Family Tomb, Covington, LA

- 1850s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- 1880s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Headstone and Monument Restorations, Pensacola, FL

- Society Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Education

- Blog

- Contact

|

Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC is a preservation contractor in New Orleans, Louisiana, specializing in historic cemeteries, stone conservation, educational workshops and lectures. Oak and Laurel serves the region of the Southeastern US.

|

QUICK LINKS |

CONNECT |

Proudly powered by Weebly