|

During Mardi Gras season, New Orleans sees increased tourist traffic to one of its most popular attractions: its cemeteries, particularly Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 and St. Louis Cemetery No. 1. It nearly seems counterintuitive to visit a place of death and remembrance on a trip so populated with mirth and celebration. Yet the relationship of New Orleans cemeteries to its carnival celebrations is much richer than simply beads on wrought iron or the odd Muses shoe left on a tomb shelf. While the Carnival celebration is one of life and vivacity, the themes of mortality and cemeteries often creep into the mix. From death-themed floats, krewes, and costumes to actual celebrations in the cemeteries themselves, our cities of the dead have been part of the Mardi Gras stage since the 19th century.

The first (and last) Jewish man to serve as Rex in New Orleans’ Mardi Gras, Salomon later moved to New York, although he visited New Orleans each year for Mardi Gras for decades after his reign. He died in 1925 and, surprisingly, it appears as if no one knows where he was buried. His final resting place seems to remain a mystery. His sister Delia, however, married local liquor dealer Otto Karstendiek and, upon her death in 1866, was buried in the only cast-iron tomb in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. Lewis Salomon was remembered as the first Rex for decades after his great parade. And although his final resting place may remain a mystery, it stands to reason that it does, in fact, exist someplace. Unfortunately, neither of these things were true for the third King of Carnival, Rex 1874, A.W. Merriam.

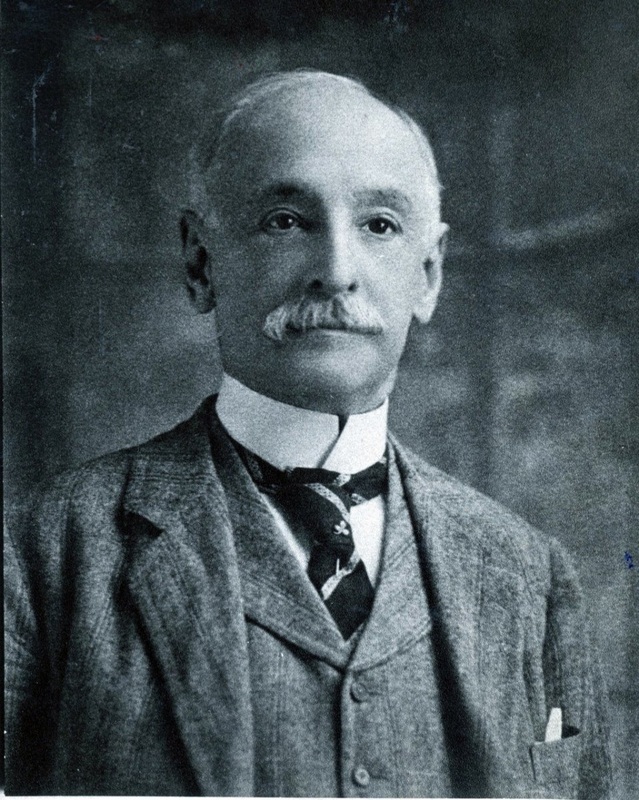

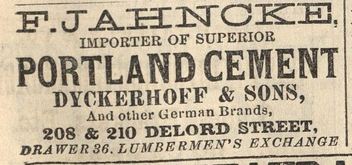

Merriam’s funeral was held days later and, in an even more tragic turn of fortune, his moral remains were paraded to Girod Street Cemetery, where he was interred.[1] While the old king may have rested in peace for as long as seventy years, Girod Street Cemetery was demolished in 1957. Whether the remains of A.W. Merriam were transferred to Hope Mausoleum (as all unclaimed remains of white people reportedly were) or elsewhere, or at all, is anyone’s guess. No record concerning Girod Street Cemetery includes his name. Rex rules his chaotic kingdom for a day. He is emblematic of both disarray and refinement, satire and grace. Upon the close of the evening on Shrove Tuesday, when Rex has met with the Court of Comus and the curtain is drawn on the season, Rex relinquishes his rule until next year, when he returns in the guise of another man. For most of those who served as Rex, death and burial was a rather uneventful affair. Yet one King of Carnival would have a much greater impact on the cemeteries of New Orleans than simply being buried there. The Builder King In 1915, Mardi Gras took place on February 16. Rex this year was Ernest Lee Jahncke, who “headed the procession on a golden chariot of state symbolic of his imperial power… crowned with jewels and wearing a mantle of cloth of gold, [sitting] upon the throne in the center of the car, gracefully acknowledging the plaudits of his subjects.” The theme that year was “Fragments from Sound and Story,” and featured such floats as “The Fatal Kiss of Undine (the water nymph)” and “The Barter of Mephistopheles,” illustrating the bargain of Dr. Faust with the devil.[2] Rear Admiral (USNR) Ernest L. Jahncke (1878-1960) served as assistant secretary of the Navy from 1929 to 1933 and was himself a “renowned yachtsman.[3]” He was the son of Fritz Jahncke (1847-1911), a German immigrant and founder of Jahncke Navigation Company. The elder Jahncke was instrumental in one of the greatest shifts in tomb construction in New Orleans history. Beginning in 1879, Jahncke was one of the first building supply dealers to make Portland cement available for his clients. While Portland cement had been available elsewhere in the country as early as the 1860s, its use was nearly unheard of in New Orleans prior to Jahncke’s business. Since the 1700s, builders in New Orleans cemeteries used mortars, stuccoes, and renders mixed from hydrated lime, a material procured from burning limestone or oyster shells in a kiln. These materials required protection from the elements, usually achieved by limewashing tombs on a regular basis.

The materials which Fritz Jahncke had made available to New Orleans cemetery builders would eventually replace lime-based stuccoes and shift the way tombs were constructed. Just as importantly, Jahncke established himself as a great paver, paving sidewalks and streets using new cement mixes and replacing the brick and shell-lined avenues that once marked neighborhoods and cemeteries. These materials in cemeteries cut down on the need to mow grass or perform other landscaping. An unintentional consequence of this paving process was the exacerbation of drainage issues in cemeteries which continue to this day. The Jahncke family expanded from serving as Mardi Gras royalty a century ago to owning a shipyard and a dry dock in addition to the cement company. Ernest continued these businesses into the twentieth century and long after his reign as Rex. He was, however, the Rex spokesperson who, in 1942, announced that Mardi Gras would be cancelled that year in the spirit of solemnity and frugality in the face of World War II. Both Ernest and Fritz Jahncke are buried in Metairie Cemetery. In the next installment of our examination of New Orleans cemeteries in Mardi Gras history, we bring death to the party itself and check out cemetery and mortality-themed floats, krewes, and costumes.

9 Comments

Gayl

1/14/2018 12:39:53 pm

Emily, I have a photo of the REX Court 1929. Both King William Henry McLellan and Queen Beecye Casanas Toledano buried in Lafayette #1.

Reply

Emily Ford

1/16/2018 07:47:45 am

That's so cool Gayl!! I'd love to see them sometime. I think I've seen one of two photos of Beecye, but not of McLellan.

Reply

Holley

10/25/2018 10:34:09 pm

Hi! William Henry McLellan is my great great uncle. Any chance I could see the photo? I'd love to see the 1938 Rex court where my great grandfather was king.

Reply

Emily Ford

10/26/2018 08:02:45 am

Hey Holley! I'll get in touch with Gayl and see if I can't put you in touch or otherwise send you a copy. 2/14/2018 11:45:56 am

Please disregard and delete my earlier messages. I am working on some Salomon genealogy and confused the same with next generation information. Thank you for the splendid photo of Mr Salomon (above).

Reply

2/14/2018 12:17:46 pm

Okay, Emily. Starting over on Lews J Salomon. Born 09/24/1838 in Mobile. Died 05/04/1925 in Far Rockaway, NY. Married to Theresa King (Friedman) of Philadelphia on 12/23/1880 in NY City. NY State record of marriage gives his name as Lewis Jacob Salomon. Death record gives his name as Lewis Joseph Salomon. DAR info shows him as Lewis Jackson Salomon. His father was in business in Mobile at time of his birth, with Lewis Judson. Best guess?

Reply

Emily Ford

2/16/2018 07:36:03 am

Hi Mr. Carter! This does look like the same Lewis Salomon. I'm not familiar with his father's background, but that he would be in Mobile in business from New York would make sense, for sure.

Reply

John

2/18/2019 07:23:40 am

Reply

Emily Ford

2/18/2019 01:30:10 pm

Dear John, noted and corrected! Thanks for the info.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

About the Author:Emily Ford owns and operates Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

- About

-

Restoration

- Services

-

Portfolio

>

- Turning Angel Statue, Natchez, MS

- Ledger Monument, Baton Rouge, LA

- Pyramid Statuary, New Orleans, LA

- Bronze and Granite Monument, Carville, LA

- Box Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Vernacular Concrete Monument, Pensacola, FL

- 1830s Family Tomb, Covington, LA

- 1850s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- 1880s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Headstone and Monument Restorations, Pensacola, FL

- Society Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Education

- Blog

- Contact

|

Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC is a preservation contractor in New Orleans, Louisiana, specializing in historic cemeteries, stone conservation, educational workshops and lectures. Oak and Laurel serves the region of the Southeastern US.

|

QUICK LINKS |

CONNECT |

Proudly powered by Weebly