|

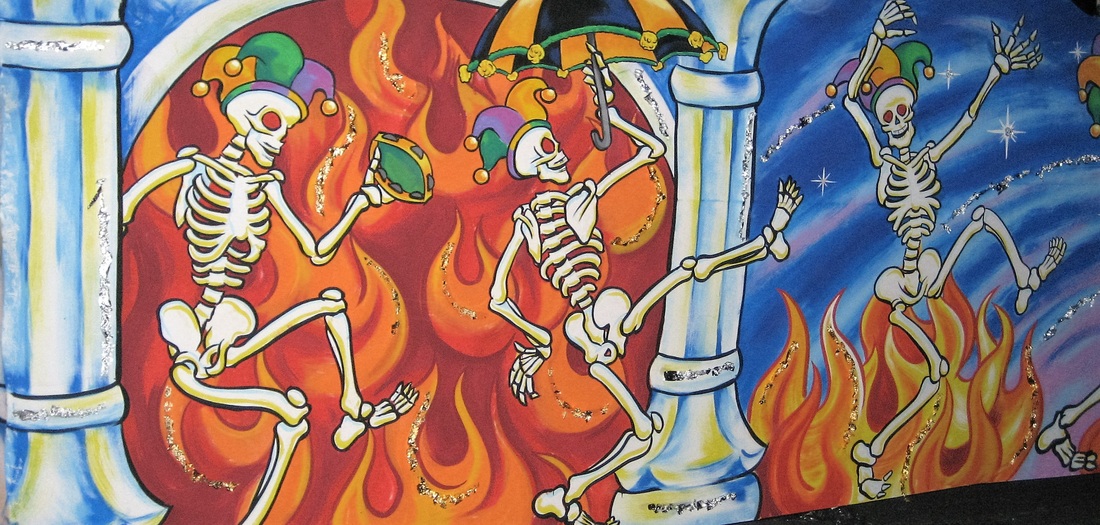

Carnival traditions like Mardi Gras and its Old World predecessors originate in Catholic pre-Lenten traditions and even pre-Catholic pagan traditions, each of which focused on the reversal of social and class roles, enjoyment of the senses, and indulgence in the face of repentance and self-denial (be that in the form of the Lenten tradition or the last months of winter without fresh meat and vegetables). In both ancient and modern contexts, Carnival is traditionally a time of celebration of life, focusing on earthly delights in the face of mortality. Yet despite these overarching themes, death and cemeteries still creep in. Beginning in Europe and later thriving in New Orleans, death has a habit of crashing Mardi Gras parties. The Triumph of Death in Florence In 1930, the Times-Picayune related an age-old story of one of the most famous appearances of Death at Carnival, in Florence, Italy, in the early 1500s: Then, suddenly, there came in sight a fiery procession, every member of which carried a torch. Under the torch flame it could be seen that every rider wore a death’s head and a black shroud. The death’s march came closer, and the horrified spectators saw that halfway down the line of parade was a covered cart drawn by four oxen, all four hung with black cloths painted with skulls and crossbones… On a pedestal in the center of the roof [of the float] stood the figure of Death, with the light the torches streaming through his hollow eye-sockets and empty ribs, and in his hand his scythe. At his feet lay six open coffins, within which could be seen six bodies wrapped in shrouds… When the procession reached the public square the skeleton attendants blew a trumped blast, and the shroud-wrapped bodies stood up in the coffins and chanted: “As ye see us, dead we be; Dead like us, ye we’ll see; We have been just as ye, Ye shall be just as we.”[1]

The famous Triumph of Death parade occurred in either 1511 or 1512 – one account states 1506 – and was engineered by the painter Piero di Cosimo (1462-1522). Di Cosimo was recently referred to as “the strangest master of the Florentine Renaissance,” by an author that counted the Triumph of Death parade as one of his accomplishments. Most of this history of di Cosimo’s life comes from 16th century artist and historian Giorio Vasari. Vasari’s account of the parade describes a car (float) decorated by di Cosimo to appear as “a mobile cemetery,” from which the costumed dead would spring from either tombs or caskets, and sing to the spectators of their inevitable mortality. The procession was “designed to terrify, but it also provided shock value and gruesome entertainment.[2]”

Although 1506-1512 represented a lull in the ever-occurring waves of Black Plague epidemics, the presence of death was never too far from the Florentine consciousness. Piero di Cosimo himself is assumed to have died of plague in 1522. That the Times-Picayune revived this four century-old tale for Mardi Gras 1930 is not entirely surprising. By this time, death was already marching in the parade. Beyond a strange 1911 incident in which a parade actually took place in St. Louis Cemetery No. 2 (to be discussed in our next blog post), the ranks of Mardi Gras Indians had already, by this time, included a tribe of ghostly marchers. Deathly Maskers The North Side Skull and Bones Gang has its origins in the early 19th century and developed in the early 20th century alongside other African American Mardi Gras traditions like the Baby Dolls and Mardi Gras Indians. In a tradition that continues today, members of the North Side Skull and Bones Gang wake up before dawn on Mardi Gras day and parade from the Backstreet Cultural Museum through the Tremé neighborhood ringing bells, shaking rattles and shouting, dressed as skeletons. Much like the Renaissance parade of Florence, the North Side Skull and Bones Gang reminds us all that “death is always lurking, and sooner or later, it will come knocking at your door.”

The Skeleton Krewe marches on Mardi Gras day down St. Charles Avenue and into the French Quarter. This interview by photographer Julie Dermansky with Skeleton Krewe founder Christopher Kirsch describes the history of the Krewe of black-clad skeletons with enormous papier-maché skull masks. In its classical purpose as a time of celebration and role reversals, Mardi Gras is a time where anyone can be anything they want to be. New Orleans’ great tradition of costuming emerges in full force, and the expression of so many human experiences bursts forth – be it in the form of vivacious parades or celebrations of death. From Renaissance Italy to the Tremé neighborhood of New Orleans, the grim reaper has frequently had a place at the parade. And dressing as a New Orleans tomb for Mardi Gras? Apparently, that too has been done. Next time we visit New Orleans cemeteries in Mardi Gras traditions, we look at times when the party entered the cemeteries themselves – the St. Louis Cemetery No. 2 Marching Club, and a mad cemetery caretaker. [1] “Mardi Gras Joke Once Placed Ban on Night Parades: Comus Carries on Despite Florentines’ Strange Sense of Humor,” Times-Picayune, February 2, 1930, p. 28.

[2] Landon, William J., Lorenzo di Filippo Strozzi and Niccolo Machiavelli: Patron, Client, and the Pistola fatta per la peste (University of Toronto Press, 2013) 49-52.

2 Comments

2/26/2017 12:03:31 pm

Great stories, insights into human fears, coping skills.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

About the Author:Emily Ford owns and operates Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

- About

-

Restoration

- Services

-

Portfolio

>

- Turning Angel Statue, Natchez, MS

- Ledger Monument, Baton Rouge, LA

- Pyramid Statuary, New Orleans, LA

- Bronze and Granite Monument, Carville, LA

- Box Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Vernacular Concrete Monument, Pensacola, FL

- 1830s Family Tomb, Covington, LA

- 1850s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- 1880s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Headstone and Monument Restorations, Pensacola, FL

- Society Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Education

- Blog

- Contact

|

Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC is a preservation contractor in New Orleans, Louisiana, specializing in historic cemeteries, stone conservation, educational workshops and lectures. Oak and Laurel serves the region of the Southeastern US.

|

QUICK LINKS |

CONNECT |

Proudly powered by Weebly