|

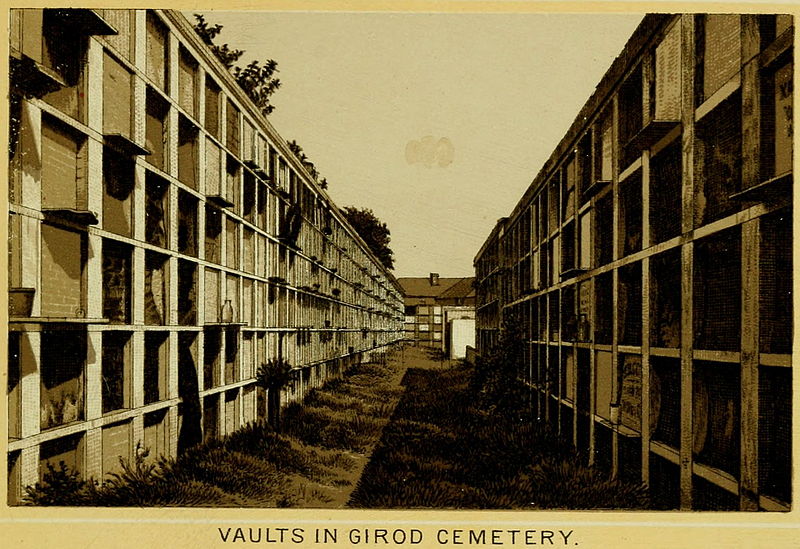

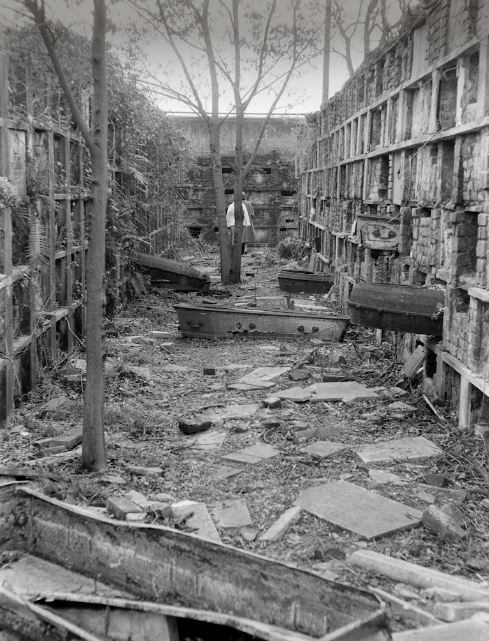

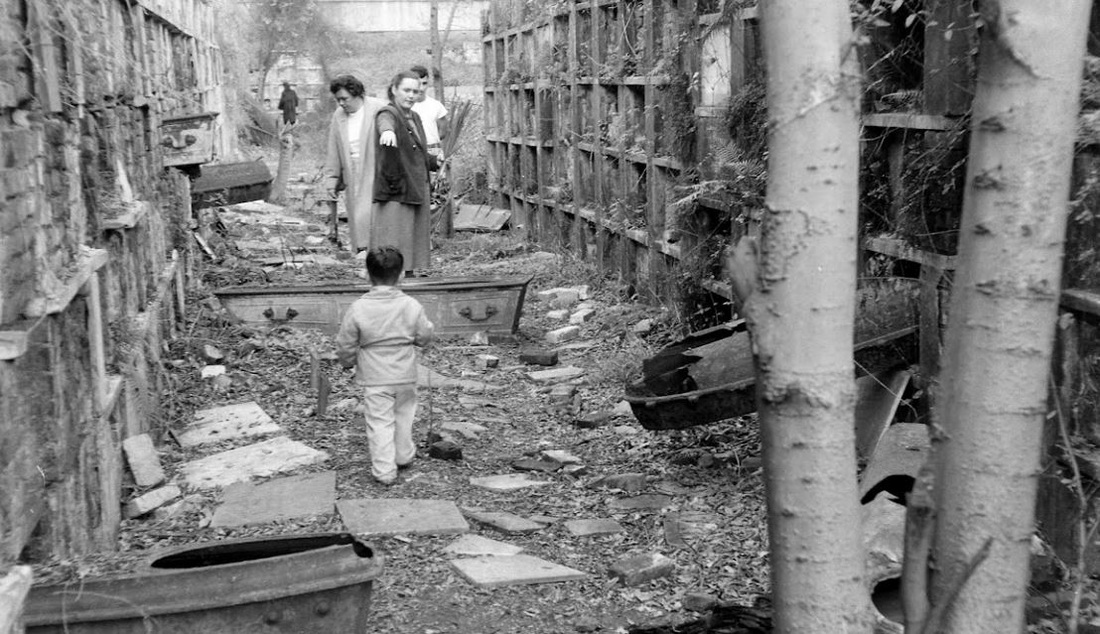

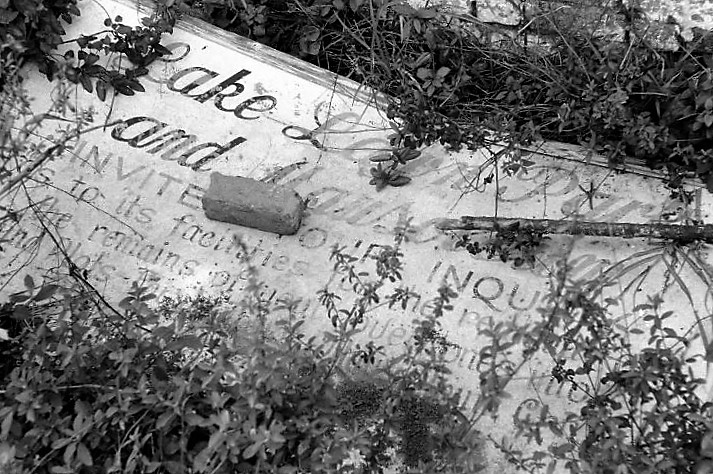

This blog post was inspired by the photos within, most of which were taken by Robert W. Kelley of LIFE Magazine in 1957. These images show Girod Street Cemetery in its final moments, as well-dressed adults and children mill around its collapsed tombs and open vaults, with newly-built New Orleans City Hall present in the background of many shots. Mis-labeled “Gerard” Street Cemetery, they offer a vignette of what has long since disappeared from the New Orleans landscape. The full album can be found via Google Cultural Commons here. The topic of Girod Street Cemetery is one that comes up in a few varieties of conversation among New Orleaneans, most often related to the charming notion that the Louisiana Superdome was built atop the burial ground (it wasn’t, per se). The relationship of the old cemetery, known also as the Protestant Cemetery, to the New Orleans Saints football team is one that has been described many times over, best by Richard Campanella and Doc Boudin of Canal Street Chronicles. Check them out to see why you can’t blame the vengeful dead for a losing season. The Protestant Cemetery, 1822 – 1940 The former footprint of the cemetery, however, was indeed quite close to the present-day Superdome. Originally bounded by Liberty, and the former Cypress and Perillat Streets, the cemetery once stood beneath where Superdome parking garages and the Champions Square complex now rise. Founded in 1822, this once-distinctive cemetery lay at the terminus of Girod Street. Previous to that date, non-Catholics were buried in the rear of St. Louis Cemetery No. 1. The narrow “Protestants Section” in St. Louis No. 1 was once much longer, but was truncated after construction to Treme Street in 1820. Shortly afterward, Episcopal Christ Church was awarded the land that became Girod Street Cemetery. Over the course of the nineteenth century, Girod Street Cemetery developed into a landscape distinct from its New Orleans cemetery sisters. As the second-oldest cemetery in the city, it amassed the vestiges of early cemetery architecture, from single-vault, stepped-roof structures to more ambitious marble-clad and Classically inspired sarcophagus tombs. The tomb of Angelica Monsanto Dow, who died in 1821, reflected this aesthetic well. Girod Street Cemetery furthermore was an “American” cemetery, in that it became the final resting place for many New Orleans residents who had travelled from elsewhere, particularly the Anglo-American north and Midwest. From these outsiders came tombs and materials inspired by northern cemetery designs – clean, wire-cut Philadelphia brick, liberal use of stone urns and many, many obelisks. Girod Street Cemetery kept within its walls a tableau of cemetery artisanship that stood out from the landscapes of its sister Catholic, municipal, and fraternal cemeteries. Through the nineteenth and into the twentieth century, Girod Street Cemetery would become the final resting place for many New Orleaneans of distinction. Heroes of the Mexican American War, civic leaders, and prominent families utilized the burial ground. One estimate suggested that the cemetery was once home to 100 society tombs. For comparison, Lafayette Cemetery No. 2, which is usually noted for its society tombs, has just twenty. In Girod Street Cemetery, the tomb of the New Lusitanos Benevolent Society was likely the most notable. Designed by J.N.B. de Pouilly and erected in 1869, the tomb had 100 vaults and a walk-in vestibule framed with a Classical portico. Being somewhat centrally located, Girod Street Cemetery was also heavily utilized as a public burying ground in times of epidemic. It seems as though nearly every major epidemic of the nineteenth century involved a terrible debacle at Girod Street Cemetery, in which bodies were stacked beyond capacity with no one to bury them. This may have also been due to the presence of a de facto Potter’s Field adjoining the cemetery, which was described as early as 1837: “This latter receptacle of the dead [the Protestant cemetery] has for many years been a disgrace to New Orleans. Once the Potters’ Field, it soon became the public burying ground, provided you were able to pay for a vault – otherwise you had to be sent further out into the swamp.”[1] The 1833 cholera epidemic in New Orleans proved especially tragic for Girod Street Cemetery, although it was not necessarily the last time the cemetery fell prey to insufficient manpower in the face of great loss of life: … the unshrouded dead dumped at the gateway of the Girod Street Cemetery accumulated in such numbers that the entrance to its precincts was so obstructed that arriving bodies had to be deposited on the outside; no graves at this time could be dug; no coffins were procurable, for there were neither grave diggers to be had nor undertakers to be found. The City Council was forced to order out the chain gang ‘prisoners’ from the city jails, to dig a trench the whole length of the lower side of the cemetery. It was dug some twelve or fifteen feet wide, and as deep as the filtering water soil would permit, into this receptacle the decomposing bodies were dragged by hooks from the fire companies, without the formality of precedence or order of any kind. As a part of the trench was filled, the earth taken from it was heaped upon the remains of the rich and the poor, the aged and the young.[2] This mass grave would eventually be erroneously referred to as the “yellow fever mound” in later years. In the late 1940s, historians would determine that this feature was in fact the burial of 1833 cholera victims.[3] The Back of the Swamp Girod Street Cemetery, for its stately obelisks and high society residents, would be plagued with issues surrounding its management and topography for most of its existence. In the 1830s, only years into its functional life as a cemetery, it would be noted that its vaults were built with only one brick thickness to their walls, which permitted the “escape of unhealthy odors.”[4] However this was not an issue exclusive to Girod Street – City ordinance did not regulate the quality of tomb construction until the 1850s. What did afflict Girod Street perhaps more than other cemeteries was its location in significantly low-lying land. Girod Street Cemetery swelled with feet of water in Sauve’s Cravasse of 1849, and frequently took on water in other instances, owing to its place on swampy land. In 1880, a special commission of Louisiana state representatives assessed the condition of New Orleans cemeteries and found them all to be in “proper” condition – with the exception of Girod Street Cemetery. Noting, “in the event of rain [Girod Street Cemetery] is always flooded to such an extent that it will affect the sanitary precautions necessary to prevent the contracting or spreading of any diseases,” the commission recommended the cemetery be closed. This recommendation was apparently declined.[5] Girod Street Cemetery’s troubles would not end there. The Fall of Girod Street Cemetery Through the course of its existence, Girod Street Cemetery was owned and operated by Christ Church Cathedral. Until the mid-twentieth century, most religiously-affiliated cemeteries were managed by the respective congregation that owned them. These congregations appointed a sexton or caretaker to manage them by performing burials, building tombs, and keeping records. Although city law required sextons to compile records to be submitted to the Board of Health, the interment records of each cemetery were kept by each sexton to varying degrees of organization. At the turn of the century, increasing industrialization of the monument trade shifted the role of sexton away from groundskeeper and toward that of a sales agent. In some cases, this meant a decline in peripheral duties. This shift is often credited for the lessening of care for the cemetery, as is the inclination of families to move their loved ones remains to newer cemeteries (namely Metairie Cemetery, established 1872). Lack of sellable space and changing racial demographics in the neighborhood of Girod Street Cemetery are also noted as causes for decline. For any combination of these reasons, or others, the administration of Christ Church found themselves in a difficult bind with their cemetery.[6] By the early 1940s, reports on the condition of Girod Street Cemetery appear to have drastically worsened. Wrote one reader in a 1943 letter to the Times-Picayune: … I was horrified to find many of the tombs broken open and others completely destroyed. There was a large fire burning at the top of one of the tombs. I saw what looked like wooden boxes burning. The cemetery looks more like a poultry farm. Atop the tombs are a number of chicken coops, and chickens wandering everywhere, and some of the lovely trees are completely or nearly burned down. Where are the owners of these tombs, that such desecration is allowed? And who cares for this unfortunate burying place?[7]

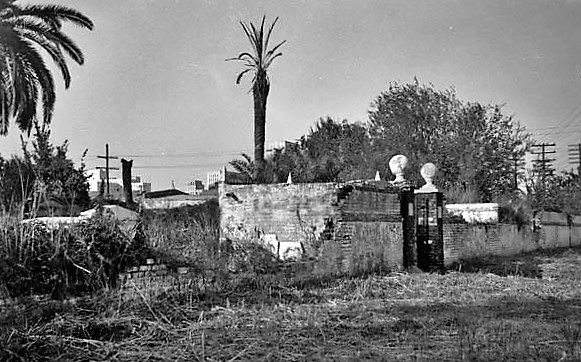

By the time of this announcement in 1947, Girod Street was merely joining in a much larger phenomenon in which cemetery management was drastically changing. In 1945, the City of New Orleans eliminated the position of sexton from the six municipal cemeteries. In the years following, former sextons and stonecutters would go into business for themselves as cemetery owners, profiting primarily from streamlined materials and low overhead costs. This process was best accomplished by Albert Weiblen, who eventually purchased Metairie Cemetery, and the Stewart family, who built Lake Lawn Park in the 1950s. However, this approach relied on the cemetery having lots available for sale. The last sexton of Girod Street Cemetery, Eugene Watson, died in 1950. In 1948, Christ Church ran multiple notices enjoining tomb owners to repair their property. However, as the cemetery owners pushed to bring the burial ground into the twentieth century, they would stumble over technicalities of property ownership, prohibitive costs, and a booming, modernizing world slowly encroaching on the Girod Street walls. “An Eyesore in the Midst of Progress” The Post-World War II era brought huge changes to nearly every facet of American life. In the cemeteries, everything from materials to business models to the funeral industry transformed. In the American city, revolutionary ideas of urban renewal swept through downtowns, destroying historic districts and erecting aggressively modern new landscapes. In New Orleans this urban renewal took place with mayor deLesseps “Chep” Morrison, and it took place along Loyola Avenue, where historic buildings were swept away for a new library, city hall, and train depot. The intersection of Liberty and Girod Street, at the boundary of the cemetery, was awkward and could not adequately accommodate recently increased truck traffic volumes. By the late 1940s, even the federal government eyed the Girod Street property as a potential site for a new post office and federal building. In the light of rapidly encroaching superhighways and new urban landscapes, Girod Street Cemetery became even more anachronistic. Perceived as an affront to the bright future of the city’s civic heart, plans to renovate the cemetery fizzled into outright demolition by neglect, aided by the agenda of modern city leaders. Lack of care led to vandalism, which led to inevitable decries that the cemetery was too broken to be fixed. In June 1948, city workers arrived at Girod Street Cemetery and knocked enormous holes in the perimeter wall, hauling away five truckloads of bricks. After protests from Christ Church, Mayor Morrison simply responded that he didn’t realize there would be an objection.[12] In 1954, the City of New Orleans successfully expropriated more than twenty thousand square feet of the cemetery for the purposes of widening Liberty Street. In addition to this seizure of land, city council furthermore requested the mass removal of all remains from the cemetery entirely, and that they be removed to newly-finished Lake Lawn Park, a for-profit venture of the Stewart family.[13] Girod Cemetery is Calling Days after the announcement of the expropriation, city attorneys placed ads in newspaper enjoining any person with family buried in Girod Street to contact the City. Attempt to salvage burials, tombs, sculpture, and any other remaining resource of the cemetery were launched. Many of these reburials had already taken place in years previous by families who suspected the cemetery’s demise. In 1955, the remains, tomb, and monument of Lt. Col. William Wallace Smith Bliss was removed to namesake Fort Bliss in Texas. The Louisiana Landmarks Society led this effort, as it did other efforts to locate families associated with the cemetery. In June of 1955, the city officially purchased the cemetery. In January 1957, it was deconsecrated. Only months later, Louisiana Landmarks member and remarkable cemetery historian Leonard Victor Huber decried the demolition process at the cemetery: “Another 60 days and there will be nothing left of Girod Street cemetery but a memory. Tombs are being broken up… I was in a garden recently with its walls built of marble slabs from the cemetery.[14]” Through the course of demolition, remains of white descent were reinterred at Hope Mausoleum, owned by Leonard V. Huber. African American burials were removed to Providence Memorial Park. In October 1958, Christ Church sold 96,000 remaining square feet of the cemetery to the federal government for nearly $300,000. This sale would transform sections of the cemetery into a parking garage for a planned post office and federal building on Loyola Avenue. Said Frank Schneider of the Times-Picayune, “Girod became an eye sore in the midst of progress but now it will contribute something to New Orleans’ changing skyline. The 14-level post office structure will be the largest federal building in the Deep South.”[15] Learning from Girod Street Although certainly accelerated by ambitions of new urbanism, the issues that led to the demolition of Girod Street Cemetery are the same issues that regularly appear in discussions of historic cemetery management today. The power of the cemetery authority to manage abandoned tombs and lots is a topic of constant contention. Cemetery owning bodies today can write off issues of abandonment by appealing to private property rights, and nearly in the same breath demolish lots that become hazardous or inconvenient to redevelopment. The ability to be conveniently selective regarding Louisiana cemetery law has, in many cases, enabled neglect. This neglect, of course, contributes to cyclical issues of cemetery vandalism, which often goes unabated until conditions are perceived as unsalvageable. The sweeping demolitions that took place across the United States during the 1940s through the 1960s spawned a revitalization of the American historic preservation movement. Iconized by the demolition of Pennsylvania Station in New York in 1963, fatigue over the loss of entire historic districts led to the passing of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 which, among other things, would have likely prevented the Federal government from purchasing portions of Girod Street Cemetery. The tale of Girod Street Cemetery is comprised of much more than a haunted sports arena. For cemetery preservationists in New Orleans, it is a cautionary tale that should never be too far from one’s mind. The stunted successes and disappointing failures could easily revisit any of our burial grounds. [1] “New Orleans Grave Yards,” The Picayune, September 19, 1837, 2.

[2] Daily Picayune, August 21, 1885, 2. [3] Leonard Victor Huber and Guy F. Bernard, To Glorious Immortality: The Rise and Fall of Girod Street Cemetery, New Orleans’ First Protestant Cemetery, 1822-1957 (New Orleans: Ablen Books, 1961). [4] “New Orleans Grave Yards,” The Picayune, September 19, 1837, 2. [5] Louisiana State House of Representatives, Official Journal of the Proceedings of the House of Representatives of the State of Louisiana (New Orleans: The New Orleans Democrat Office, 1880), 285. [6] “The Crumbling World of Girod Cemetery,” Dixie: Times-Picayune States Roto Magazine, August 29, 1954, 6-7. [7] “Historic Cemetery Neglected,” Times-Picayune, June 23, 1945, 10. [8] “Old Cemetery to be Rebuilt,” Times-Picayune, December 21, 1947, 3. [9] “Threaten Razing of Vaults, Tombs, Fate of Old Cemetery to Rest with Lot Owners,” Times-Picayune, October 23, 1945; “Girod Cemetery Inspection Made,” Times-Picayune, October 30, 1945. [10] “Zulu Chief’s Wish to be Buried with Pomp and Ceremony Fulfilled,” Times-Picayune, August 23, 1948, 24. [11] “Old Cemetery to be Rebuilt,” Times-Picayune, December 21, 1947, 3. [12] “The Crumbling World of Girod Cemetery,” Dixie: Times-Picayune States Roto Magazine, August 29, 1954, 6-7. [13] “Girod Cemetery Strip is Sought,” Times-Picayune, November 12, 1954, 1. [14] “Up and Down the Street: Book on Girod Cemetery Needs Help,” Times-Picayune, August 15, 1957, 19. [15] “Old Burial Spot is Sold as Site for U.S. Garage,” Times Picayune, October 4, 1958, 11.

40 Comments

Ron

7/17/2016 08:33:35 pm

Hi,

Reply

7/18/2016 08:14:22 pm

Dear Ron,

Reply

Ron

7/18/2016 09:02:26 pm

You could upload the PDF to oakandlaurel.com...

Ron

7/18/2016 09:04:01 pm

What I mean is that what you uploaded was the address of the PDF on your -- or someone's -- local computer.

Gay R. Pearson

7/18/2016 01:28:04 pm

A sad but interesting historyof Girod St Cemetery. My great great grandparents were buried there in 1884.

Reply

Shackthrow

7/18/2016 10:32:37 pm

I wish they had superimposed the precise location of the cemetery over a current day map.

Reply

7/20/2016 10:37:25 pm

Me too! But why reinvent the wheel when it's already been invented by New Orleans' geographer laureate Richard Campanella:

Reply

Robert L Treadaway

8/5/2019 12:26:04 pm

The location is in part where the superdome and smoothie center are now

Reply

Ron

8/5/2019 12:29:08 pm

So it's not an INDIAN burial mound that cursed the Saints (and now the Pelicans) for so long...

Paul

7/19/2016 11:00:45 pm

Thanks so much for writing and posting this. I really enjoyed it.

Reply

Stacey hebert

7/20/2016 05:00:58 am

I had family buried there once but was moved to Metairie Cemetery. It is a shame that a historic cemetery was not kept up at least by the city

Reply

10/13/2017 07:03:02 pm

Great read! So sad to see history fall by the wayside. Sadly, I have seen some cemeteries here in New Jersey suffer the same fate.

Reply

Ron

10/13/2017 07:26:53 pm

"Only months later, Louisiana Landmarks member and remarkable cemetery historian Leonard Victor Huber decried the demolition process at the cemetery"

Reply

Emily Ford

10/13/2017 07:30:12 pm

I think maybe I could have been clearer on the wording of that sentence. Leonard Huber was a vocal advocate for Girod Street Cemetery through the whole process. In fact, I often reflect about how Louisiana Landmarks doesn't take enough credit for their fight to save Girod Street Cemetery. Huber later wrote a book entitled "To Glorious Immortality" about Girod Street Cemetery. It's a treasure of a book.

Reply

Callie B. McGinnis

1/20/2018 03:57:24 pm

Do you know if Christ Church (or anyone else) has interment records for Girod? I know that one of my ancestors (Robert Murphy) was buried there. I'm curious about some of my other New Orleans ancestors -- whose resting places I cannot find; all of whom lived not to far from Girod. Thanks, Callie

Reply

Callie B. McGinnis

1/20/2018 04:20:55 pm

Please disregard my previous question. A google search just revealed that the burial records for Girod are at Tulane. Thanks, Callie

Reply

Emily Ford

1/20/2018 05:05:47 pm

Dear Callie,

Reply

9/12/2018 07:56:01 am

Hello! I just would like to give a huge thumbs up for the great info you have here on this post. I will be coming back to your blog for more soon.

Reply

Diane Dixey

1/4/2019 09:22:59 am

A wonderful, cautionary read... Thank you

Reply

Marc Champagne

2/18/2019 09:35:17 pm

Thanks for this enlightening story. I am from the New Orleans area and had no idea about this cemetery. I currently live in Alexandria but spent some of my childhood in N. Little Rock. My maternal grandmother is buried in Oakland Cemetery in Little Rock. Beautiful place.

Reply

Karen Freeman

2/18/2019 10:20:32 pm

Thank you for sharing. I am always dismayed when reading about people’s final resting place falling victim to vandalism and neglect. Thanks to all who share this history with us and to all who volunteer tirelessly to restore resting places of people long gone.

Reply

Rory Morgan

2/19/2019 05:59:44 pm

Nice work on this piece!

Reply

Julaine Schexnayder

2/20/2019 10:29:15 am

As a cemetery preservationist., I appreciate the info being preserved in this research paper.

Reply

Anthony Langley

8/3/2019 08:11:14 pm

This is a very interesting article. Thank you for your research. Maybe I missed it, but do the records show the total number of people that were entombed there, and how many of those people were NOT claimed by relatives during the final days of the cemetery? With the cemetery being so old, I would expect that there were a large number of unclaimed bodies. After all, I don’t take regular walks through the cemeteries of my great-great grandparents, simply because I don’t know where they are buried. Therefore, I would never see a 60-day notice to begin repair work. Also, was the sexton doing his job if the place looked like a chicken farm in 1943? On a side note, l’m from Houston, but visit my grandparents’ burial place whenever I pass through New Orleans. They are entombed in the Hope Mausoleum (second floor..... no flooding).

Reply

Emily Ford

8/5/2019 09:30:41 am

Hi Anthony!

Reply

8/6/2019 10:56:37 am

A truly sad story and I have a personal family connection. My 3rd great grand aunt, Sophia Dodson Law (1842-1853), was buried in this cemetery. As of this writing, I still do not know her final resting place after she was moved from Girod. While most my family is buried in Lafayette #1 and the Metairie Cemetery, I may have had other family members in Girod that I am not aware of. It is one of those family mysteries I may never be able to solve.

Reply

RC Heath

11/23/2019 09:32:18 am

Is there any chance that you might be able to provide any information on my first cousin six times removed, Francis Asbury Lumsden, his wife Blanche Spedden Lumsden, and their two children Francis and Emma? It is alleged and written in our family bible, that all four died on board the steamer Lady Elgin on Lake Michigan, on the morning 1860 September 8. The Find A grave posting that I have found advised that, "His body was recovered, and buried at New Orleans", in the defunct, "Girod Street Cemetery (Defunct) New Orleans, Orleans Parish, Louisiana, USA". I have never been to New Orleans and have only what I have read in regards to the cemetery, which sadly looks way worse for wear. As a trained skeptic by trade, I place little emphasis on hearsay and it is entirely probable that Francis's body was not recovered and relocated to this cemetery. It also does not suggest that Blanche and the children were located and moved. Just curious to see if you could advise any detail. Thank you for your time.

Reply

Emily Ford

12/12/2019 10:04:42 am

Hi RC! I looked into some of the info available concerning the Lady Elgin, F.A. Lumsden, and Girod Street Cemetery. Sent you an email! Thanks!

Reply

Melissa Quitadamo

5/18/2020 08:57:11 pm

I have a morbid question. As I understand it, the land around the Girod Cemetery was often flooding and swampy, wouldn't the "unshouded dead" in the mass grave resurface? We see, for example, how coffins can float out of tombs and such during flooding, were there ever stories of human remains reaching the surface again? I imagine there were horrible sanitation issues as well.

Reply

Emily Ford

5/24/2020 05:43:51 pm

Hey Melissa! It is a little morbid, but on a practical level, whether a casket floats or does not depends on the seal of the casket lid.

Reply

6/2/2020 03:34:00 pm

Emily,

Reply

Emily Ford

6/2/2020 05:32:44 pm

Hey Frank! You might get in touch with the folks at Hope Mausoleum. They may be able to help you get the information on Lt. Henderson.

Reply

6/26/2020 12:23:15 am

I am trying to figure out exactly which 1957 issue of Life Magazine were the photos of the cemetery published. Do you happen to know?

Reply

Emily Ford

6/26/2020 09:40:33 am

I wish I did know. The Google Cultural Commons files note that the photos were taken by Robert W. Kelley for TimeLife. It's also part of the Robert W. Chambers collection, which includes pop culture photos from the 1950s and 1960s, most associated with Time/Life.

Reply

3/30/2023 05:55:58 am

In this blog post, the author reflects on the history and significance of Girod Street Cemetery, a once-distinctive cemetery in New Orleans. The cemetery, originally known as the Protestant Cemetery, was founded in 1822 and was the final resting place for many New Orleans residents who had traveled from elsewhere, particularly the Anglo-American north and Midwest. Over time, the cemetery became home to many tombs and materials inspired by northern cemetery designs, and it amassed the vestiges of early cemetery architecture.

Reply

Mike Saxton

10/16/2023 11:55:37 am

The Williams Research Center in New Orleans has many detailed photographs which are available for download. Search for "Girod Cemetery" at https://catalog.hnoc.org/web/arena/search#/?q=Girod+Cemetery to find them.

Reply

Mike Saxton

10/16/2023 12:11:26 pm

For those of us who can document ancestors who were buried at Girod, but were never claimed for reinterment elsewhere, be aware that Hope Mausoleum, intended as the memorial for unclaimed remains, will not allow you to visit the crypt for these remains unless you can prove your ancestor's remains are actually in their vault. Obviously, that is not possible given the history of Girod! We have personally experienced what many Yelp reviews on Hope describe as an extremely rude gentleman who will aggressively assert that you have no right to visit this memorial and yell at you to get out. I think it is very sad that the city that took this action to move remains did not ensure they could be visited by family members in subsequent years. If any of you who still live in New Orleans have any suggestions of how to address this unacceptable situation that shows a disrespect for our ancestors, please advise for everyone's benefit.

Reply

1/17/2024 07:50:34 am

Appreciate the insights into Girod Street Cemetery's past, highlighting its architectural distinctions and role as a final resting place for notable individuals. The historical context and images provide a fascinating perspective on this piece of New Orleans history.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

About the Author:Emily Ford owns and operates Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

- About

-

Restoration

- Services

-

Portfolio

>

- Turning Angel Statue, Natchez, MS

- Ledger Monument, Baton Rouge, LA

- Pyramid Statuary, New Orleans, LA

- Bronze and Granite Monument, Carville, LA

- Box Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Vernacular Concrete Monument, Pensacola, FL

- 1830s Family Tomb, Covington, LA

- 1850s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- 1880s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Headstone and Monument Restorations, Pensacola, FL

- Society Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Education

- Blog

- Contact

|

Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC is a preservation contractor in New Orleans, Louisiana, specializing in historic cemeteries, stone conservation, educational workshops and lectures. Oak and Laurel serves the region of the Southeastern US.

|

QUICK LINKS |

CONNECT |

Proudly powered by Weebly