|

New Orleans is home to dozens of cemeteries, each with its own character and history. Among these many burial and interment grounds are the influences of world cultures, human expressions of grief, and iterations of architecture that, in one way or another, are recognized as significant on small and large scales. Some are more appreciated than others. Some have been lost entirely from the landscape, such as St. Peter Street Cemetery, Girod Street Cemetery, or Gates of Prayer Cemetery on Jackson Avenue. Yet among these recognized and unrecognized burial grounds, there is one nearly always omitted, even though people walk by it and photograph it every day. Tucked behind St. Louis Cathedral and often overshadowed by the looming statue of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, is the final resting place of nineteen French navy men who died in 1857 and were re-interred at this place in 1914.

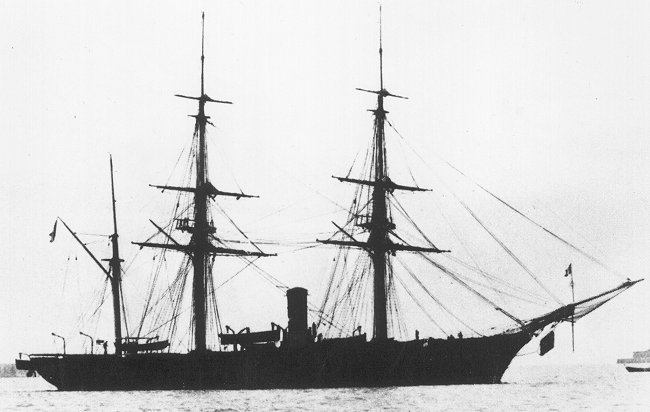

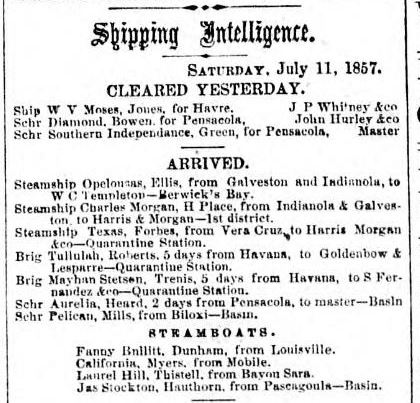

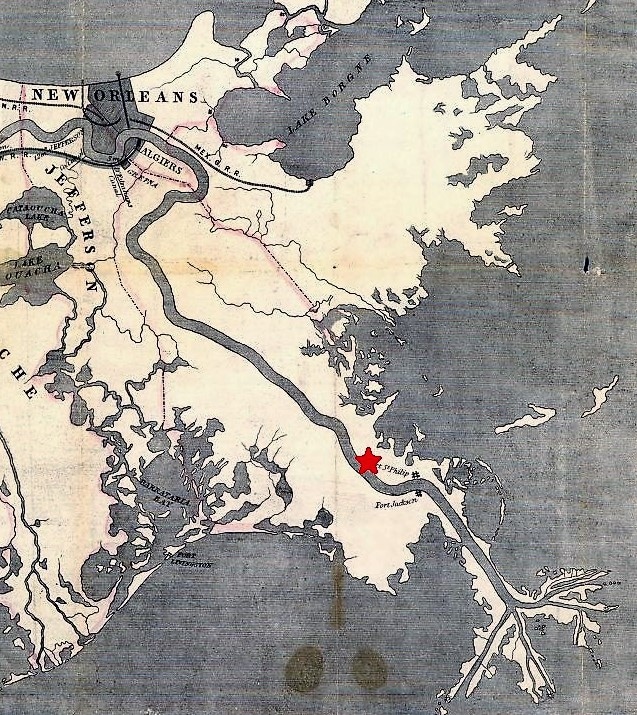

In the years following this harrowing incident, the surviving crew of the Tonnerre and their families in France, as well as French naval authorities, sought to memorialize the lost sailors. A monument was erected in the Quarantine Station cemetery in August 1859. The marble obelisk would not be seen for long, however. The Quarantine Station was soon relocated, with the former site abandoned. The monument would not be rediscovered until 1914, when Andre Lafargue endeavored to reclaim it.[3] The tale of the Tonnerre, its crew, and its monument, highlights so many historical aspects of the mid-nineteenth Caribbean and Atlantic world. It is a story of memorialization and reclamation, of the interactions between cultures and nations, and of the management of public health in this time. In this post, we seek to unpack some of these curious aspects of the monument that rises so subtly from behind St. Louis Cathedral. The Ship Tonnerre The Tonnerre is referred to in historical documents as both a corvette and an aviso or “advice ship.” While there appears to be some distinction between the two (and we don’t presume to call ourselves naval historians) – for example, avisos are customarily smaller than corvettes – documents consistently refer to the Tonnerre as a ship assigned the duty of relaying messages between larger naval commands. The four-gun Tonnerre was a steam-powered vessel, propelled by a paddle, and was inducted into service by the French Navy at Indret in 1838.[4] By 1850, the French Navy had about a dozen such first class “advice boats,” including five constructed of iron (Le Mouette, Le Heron, Le Eclaireur, Le Requin, and L’Epervier), although the Tonnerre was not constructed of iron. By 1857, the Tonnerre and its crew had already completed service in the Crimean War (1853-1856) in which an alliance of European powers fought Russia for influence over the Black Sea and Middle Eastern. Lieutenant Clement Maudet, who came to command the Tonnerre, fought with the French Foreign Legion in Crimea, earning a medal for his bravery. Many of the other sailors aboard the Tonnerre served in this conflict before being dispatched to the Caribbean. The presence of the Tonnerre in the Caribbean also highlights the colonial and military interactions in the Caribbean and Atlantic world at the time. The Tonnerre was charged with relaying messages between Vera Cruz and Havana (a role the ship would serve through the late 1850s).[5] The ship’s mission likely related to French economic and political interests in Mexico, which Emperor Napoleon III viewed as critical to Latin American trade access. French intervention would escalate to full on invasion in 1861, and later the unsuccessful installation of Hapsburg emperor Maximilian I. It was in this conflict in 1863, that Lieutenant Clement Maudet would die of wounds acquired in the Battle of Camerone.[6] The Tonnerre was the fifth ship of the French navy to bear this name. The first French Naval Tonnerre was the British HMS Thunder, captured in 1696. The Tonnerre under Maudet’s command in 1857 was retired in 1878. The French Navy currently operates the eighth Tonnerre, placed into active service in 2006. The Crew The Tonnerre had an original crew of eighty sailors, including a doctor (who died of yellow fever at the Quarantine Station), sailors, ensigns, stokers (steam engine operators), chefs, and mates. Eighty of whom contracted yellow fever either in Mexico, Louisiana, or Cuba. Thirty of these seamen died. Two of the chefs aboard the Tonnerre who perished in 1857 appear to have been of Italian descent: Giovanni Carletto and Jean Janotti. Ages of the men who died aboard the Tonnerre are not listed.

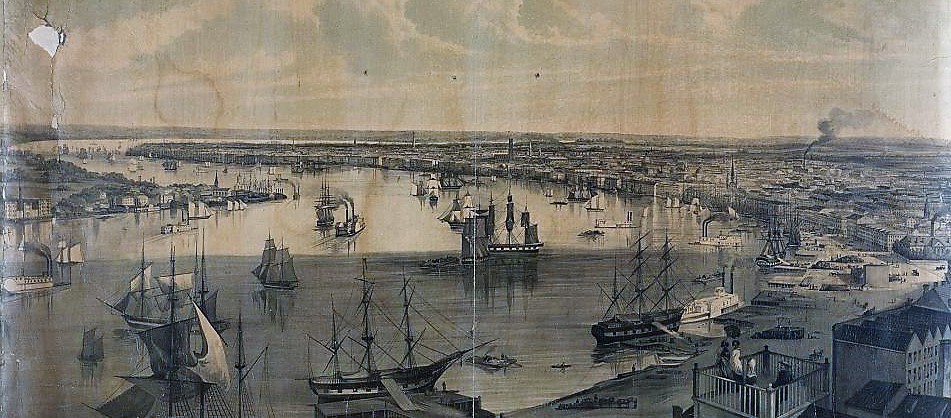

In 1853, for example, the fever was presumed to be caused by “miasmas” or “bad air” (a theory derived from Enlightenment thought), and thus the City burned torches of pitch and discharged cannons in order to disperse airborne maladies. By the 1850s, the Sanitarian movement had begun to marginally influence public health, focusing on cleanliness of public spaces and the removal of fetid water. Quarantine Stations were present in most eastern seaboard cities by the early 1800s. In New Orleans, the necessity of such stations was frequently debated and they were often decommissioned. In many cases, New Orleans merchants were staunch opponents of quarantine. Such systems, they said, disrupted commerce and were thus unacceptable. Their arguments appeared validated when, on occasion, epidemics broke out despite the presence of quarantine stations – likely due to the yellow fever mosquito (Aedes aegypti)’s fondness for sheltering in ship cargo holds. Incidentally, however, 1857 was not a significant epidemic year for New Orleans. As the Tonnerre had no intention of docking in the City en route to Havana, the condition of this one ship’s crew posed little danger of epidemic to the Crescent City.

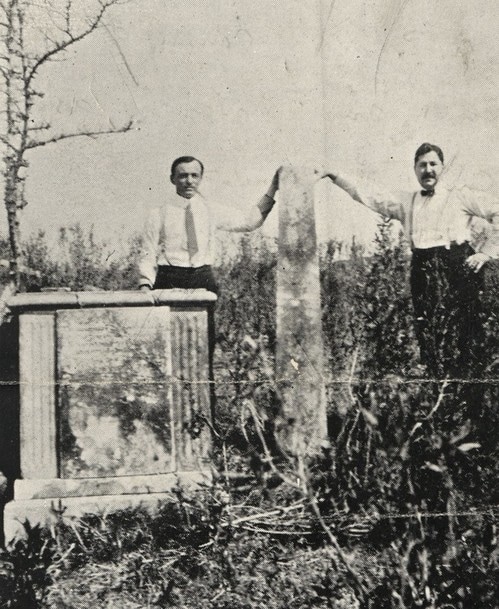

The Quarantine Station would be abandoned after the 1860s, after the US Government established an additional Quarantine Station at Ship Island, Mississippi. In 1880, the Louisiana Board of Health reported on the condition of the Ostrica-area Station, the grounds “open and roamed over by cattle.[10]” It described a complex of several buildings: a fever hospital, a pox hospital, a medical residence, a boatmen’s quarters, and a warehouse. Said the board of the process of disinfection at the hospitals: The process of disinfection now employed consists of burning sulphur in iron pots. These pots are placed in tubs containing water. This method is liable to the grave objection that there is, in many cases, and especially during rough weather, danger of firing the ship.[11] In this report, the Board of Health appears to be investigating the feasibility of placing the Station back into service, although no evidence suggests this happened. However, the report documented the enduring presence of the Tonnerre monument: The graveyard of the Quarantine Station is located about 200 feet to the rear of the Fever Hospital, and is surrounded by a rude fence and covers about three-fourths of an acre. Marks of about one-hundred graves can be discerned by the inclosure [sic], which are thickly covered with tall grass, brambles, and shrubs. There is only a solitary marble monument, which bears the following inscription: "A la mémoire de Trente Marins, faisant partie de l'équipage de l'avito vaisseau de la Marine Imperiale le Tonnerre, décède à la Quarantaine de la Nouvelle Orléans en Août, 1857. Erige par l'Odre de S.E. L'amiral Hamelin, ministre de la Marine de l'Empereur Napoléon III.”[12] The Monument Thanks to donations from the families of surviving Tonnerre crewmen, a marble monument was installed at the Quarantine Station in 1859. Unfortunately, the craftsperson that designed and built it is unknown. Photos from the monument’s recovery indicate that it was originally a marble-clad box tomb, with fluted corner pieces and a marble slab atop which the monument’s obelisk and urn were fixed. This style of memorial was typical of 1850s high-style cemetery architecture in both New Orleans and France. Derived from sarcophagus designs, similar monuments can be found in the cemeteries of Montparnasse (France) and St. Louis Cemetery No. 2, although less modified versions are visible in the upriver parishes. The Tonnerre monument was described intact by the Louisiana Board of Health in 1880, even though the Quarantine Station cemetery had become derelict. Andre Lafargue shares a similar recollection from his youth, seeing the monument ascending from the brush as he traveled the river. Lafargue notes that at some time between 1880 and 1914 the obelisk fell in a hurricane.[13] The Quarantine Station long abandoned, without intervention the Tonnerre monument would have sunken beneath overgrowth and debris. Yet in 1914, Andre Lafargue, who at that time served as the attorney for the Comité du Souvenir Francais, came across in the French Society records documentation of the Tonnerre monument. In an effort that proved fruitful if not also tremendous and risky, Lafargue chartered a boat from Buras to Ostrica, bringing with him the vice French consul general at the time, Andre Lacaze, and their wives.[14] Trudging through the brush with only a vague recollection of where the cemetery and Quarantine Station once stood, the party discovered the remains of the monument: We finally came to a spot, near a tree of greater dimensions than the others, and there found traces of former habitations, and all of a sudden our feet struck a pile of bricks and pieces of marble and we knew, after examination of the fragments, that we had finally found the spot where the cemetery stood long years before and where the monument had been built. The ladies, highly elated by the discovery, were very helpful in picking up various pieces of the pedestal and we finally located the obelisk, the main section of the most important part of the monument, and the gracefully draped urn. The urn had been wrenched from the top of the obelisk and the latter had broken into two pieces in its fall to the ground, after the pedestal and the foundation had been undermined by the elements and the rough usage of time.[15] Over the course of subsequent trips to the site and through partnerships with groups like the Societe de Bienfaisance et d’Assistance Mutuelle, the monument was packed away and sent upriver to New Orleans. Despite the contestations of local undertakers that recovery of the remains of the 19 seamen who died at the Quarantine Station would be impossible, Lafargue and his crew set out to disinter each one. Each body was laid beneath the flag of France during disinterment, then shrouded and placed together in a metallic casket, where a single French flag was draped across them. In an additional gesture of reverence, the party uprooted a small tree from the cemetery and placed it in the coffin with the remains, to be re-planted at the new monument site.[16] The monument was reconstructed by New Orleans stonecutter and tomb builder Albert Weiblen. Weiblen built a burial vault atop which the monument would sit and bordered with a Georgia Creole marble coping wall. This vault forms a tumulus structure and simultaneously elevates the monument. Weiblen’s skill in reconstructing the monument is remarkably evident: it is difficult to determine which elements of the monument are replacements and which are original. But some clues are visible: one inscribed tablet is of a slightly different type of marble, and is inscribed with a pneumatic tool, whereas the other inscribed faces of the pedestal have smaller, hand-carved lettering. It appears as if the monument itself may have been slightly downsized, it’s dimensions shaved away to remove damaged or unsalvageable elements. A small bronze plaque was installed at the front of the coping by De Lucas Monument Company at the cost of $13.[17] Since its rededication, the Tonnerre monument has survived a few more hurricanes, and an instance in the 1930s in which an inebriated driver crashed through the gates of the Cathedral garden and toppled the obelisk. But for the most part the monument (and the remains therein) have known peaceful repose, quietly situated between St. Louis Cathedral and Royal Street, so often escaping notice. [1] Andre Lafargue, “The Little Obelisk in the Cathedral Square in New Orleans,” Louisiana Historical Quarterly, Vol. 28, No. 1 (Jan. 1945), 329.

[2] Every history of the Tonnerre’s trials at the Louisiana quarantine station omits the commander’s first name. Based on other histories of the French Navy in the Baltic and Mexico, and other statistical data, the commander of the Tonnerre was most likely Clement Maudet (1829-1863), French Legionnaire, who would die later in Mexico during the Battle of Camarone, part of the Second French Intervention. [3] Ibid., 333-336. [4] John Fincham, A History of Naval Architecture, to which is prefixed an introductory dissertation on the application of mathematical science to the art of naval construction (London: Whittaker and Co., 1851), 408. [5] French war steamer Tonnerre embarks from Havana to Mexico, Daily Picayune, October 21, 1857; French war steamer Tonnerre returns to Havana, Daily Picayune, December 14, 1857. [6] This is an extremely generalized recapitulation of colonialism in the Caribbean in the 1850s. For further reading see: The Second French Intervention in Mexico, The French Intervention in Mexico and the American Civil War, and if all of this is too complicated or frustrating, just check out this fun comic. [7] Henry Rightor, Standard History of New Orleans, Louisiana (New Orleans: Lewis Publishing Company, 1900), 211-213. [8] John Duffy, The Sanitarians: A History of American Public Health (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1992), 60; Joy J. Jackson, Where the River Runs Deep: The Story of a Mississippi River Pilot (Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 1993), 55; Alcee Fortier, Louisiana: Comprising Sketches of Parishes, Towns, Events, Institutions, and Persons, Arranged in Cyclopedic Form, Vol. 2 (Century Historical Association, 1914), 337. Jackson notes quarantine stations located at Cubit’s Gap (around 1910) and a post-1920 station at the lower end of Algiers. Andre Lafargue describes a quarantine station at Pilot Town, twenty miles downriver from Ostrica, by 1914. [9] John Duffy, ed. The Rudolph Matas History of Medicine in Louisiana, Vol. II (Binghamton, New York: Vail-Ballou Press, Inc., 1962), 185-186. [10] Joseph Jones, M.D. Report of the President of the Board of Health of the State of Louisiana for the Year 1880, 14. The report also notes the success of quarantine measures for that year, including the removal of the bark Excelsior, bound from Rio de Janiero, to Quarantine, which “certainly freed the city of New Orleans from the infected crew, and in the opinion of a portion of at least of the medical profession, preserved the citizens from an epidemic.” [11] Ibid., 18. [12] Ibid., 15. [13] Andre Lafargue, “The Little Obelisk in the Cathedral Square in New Orleans,” 336. [14] John Smith Kendall, A.M., History of New Orleans, Vol. III (Chicago: Lewis Publishing Company, 1922), 1149. [15] Ibid., 338. [16] Ibid., 336-342. There is no indication that this tree remains in the garden behind St. Louis Cathedral. [17] Receipt from De Lucas Monument company to Comite Francaise, Andre Lafargue papers, MSS 552, Folder 10, Tulane Louisiana Research Collection.

5 Comments

Lenny Zimmermann

5/2/2017 01:18:48 pm

Very interesting, as always. Arguably there is another cemetery (maybe multiples, really) underneath the floor of the Cathedral itself. I'm not sure how many other local churches also have burials under their floors, usually of clergymen, but the Cathedral does, and at least has in the past, house some other burials of notables (or at least notables at the time) as well. The problem for some of those burials is that the expansions and renovations done to the Cathedral over the years has seen individuals re-interred from beneath the cathedral to St. Louis #1, presumably to be moved back, but they never were. Unfortunately the Archdiocese seems unsure of the final resting place of most of those people. I always wondered if they had plaques denoting their interment and whatever happened to those (well, other than those few that are now on the walls of the Cathedral, anyway.)

Reply

5/2/2017 05:25:39 pm

Dear Lenny,

Reply

Lenny Zimmermann

5/3/2017 01:57:39 pm

Very interesting, I didn't even think about the potential for any marker still being somewhere under the flooring. If it helps any I have the following a note on the research I'd done for one of my own ancestors that had been buried there in 1802:

Reply

Emily Ford

5/4/2017 07:31:21 am

This is very helpful! And very very interesting. Thank you for sharing this information.

Stephen Medina

6/5/2020 01:34:00 pm

Wow!

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

About the Author:Emily Ford owns and operates Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

- About

-

Restoration

- Services

-

Portfolio

>

- Turning Angel Statue, Natchez, MS

- Ledger Monument, Baton Rouge, LA

- Pyramid Statuary, New Orleans, LA

- Bronze and Granite Monument, Carville, LA

- Box Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Vernacular Concrete Monument, Pensacola, FL

- 1830s Family Tomb, Covington, LA

- 1850s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- 1880s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Headstone and Monument Restorations, Pensacola, FL

- Society Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Education

- Blog

- Contact

|

Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC is a preservation contractor in New Orleans, Louisiana, specializing in historic cemeteries, stone conservation, educational workshops and lectures. Oak and Laurel serves the region of the Southeastern US.

|

QUICK LINKS |

CONNECT |

Proudly powered by Weebly