|

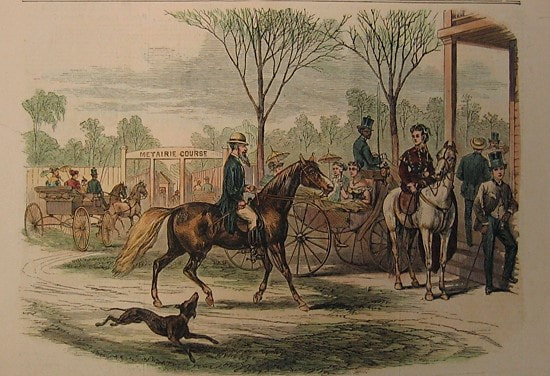

This is Part Four in a multi-part blog series examining the landscape history of what is now the intersection of Canal Street and City Park Avenue. From July to November 2017, construction will take place at this intersection to connect the Canal Streetcar to Canal Boulevard. Find Part One here, Part Two here, and Part Three here. To say that New Orleans changed drastically after the Civil War is an understatement. The economic engine of the city, which formerly relied on the institution of slavery, subsequently shifted. The city increased in population and expanded in demographics. Transportation was in the process of revolution. For the cemeteries, this period meant the industrialization of funerary craft. New materials and architectural styles appeared in cemetery landscapes, and a new kind of cemetery stonecutter would evolve. By 1930, the quiet intersection at Metairie Ridge would be transformed. Railroads, automobiles, repurposed land, and the complete disappearance of one cemetery took their effect on the landscape. The most notable monuments of Greenwood Cemetery would be erected atop a filled-in Bayou Metairie, while other sections of the bayou were converted into reflecting lagoons. But before all of this took place, the founding Metairie Cemetery would change how New Orleaneans understood their cemeteries. 1873: Metairie Cemetery Metairie Race Course had operated on the other side of the New Basin Canal from Greenwood Cemetery since the 1830s. Bounded by Bayou Metairie to the south, the race course had capitalized on the Crescent City’s appetite for sport and diversion. Yet the sport of horse racing was economically dependent on the institution of slavery: enslaved people trained racehorses, rode them as jockeys, and were even utilized as chattel in racing wagers. After the Civil War and emancipation of enslaved African Americans in the South, as well as the economic collapse heralded by the war itself, horse racing was no longer a lucrative pastime. The race course declined.[1] The end of the Civil War also enhanced cultural understandings of death nationwide. Victorian culture transformed the budding rural cemetery movement into a much larger “beautification of death” period. Cemeteries became public parks fit for day trips and picnicking. Civic notions of memorialization and mourning had brought forth new zeal for monuments and landscapes to frame them. At the same time, the craft of stonecutting and tomb building was beginning a revolution that would eventually lead to industrialization, new materials, and innovative techniques that could produce larger, more ornate tombs and monuments with less labor. All of these influences likely led to the transformation of Metairie Race Course to Metairie Cemetery in 1873. Conversely, colorful local legend often attributes the founding of Metairie Cemetery instead to the jilting of its founder, Charles T. Howard, by the Metairie Jockey Club. After repeatedly being denied membership, Howard is said to have declared he would buy the property and “make it the deadest place in town.” Yet the economic and cultural realities described above were much more likely to influence the cemetery’s founding: horseracing was no longer economically feasible, and garden cemeteries had become nationally popular. The founding of Metairie Cemetery would likely have been a matter of economic practicality. Furthermore, the founders had but to look across the New Basin Canal to the ten cemeteries nearby for inspiration.[2] Metairie Race Course declared bankruptcy in the early 1870s. In May of 1872, the Metairie Cemetery Association was formed with William S. Pike as president and Charles Howard, D.F. Kenner, W.S. Lipscomb, G.A. Breaux, and J.A. Morris on the Association’s board. By mid-1873, the Association had secured ownership of the land in perpetuity and without taxation by way of an act of the Louisiana legislature; this act also empowered the Association to punish trespassers who harmed tombs, shrubbery, or shot guns in the cemetery.[3] The Association chose architect Benjamin Morgan Harrod to design Metairie Cemetery. By this time, rural garden cemeteries were an institution of the American landscape. New Orleans had welcomed its first rural cemetery in 1840 with Cypress Grove; yet while the old Fireman’s Cemetery incorporated landscaping and horticultural features like its northern sisters, it lacked the ambling roadways and water features that so distinguished rural cemeteries like Mount Auburn, Green-wood and Laurel Hill. Under Harrod’s influence, Metairie Cemetery would emulate the northern rural cemeteries even more than Cypress Grove had. Thousands of trees were planted along the racetrack’s original thoroughfare. New roads were placed within and outside the racetrack itself, but kept with its oblong shape. Metairie Cemetery was also the first cemetery in New Orleans to be owned by a private association. To this point, all cemeteries were owned by either religious organizations (churches, synagogues), fraternal organizations (firemen, Masons, Odd Fellows), or the City of New Orleans. Charity Hospital Cemetery was owned by the state. The concept of the cemetery as a private enterprise had long been familiar outside of New Orleans, and the model of private cemetery ownership would expand in the area as time progressed.[4] Metairie Cemetery quickly became a new venue for leisure travel on the New Shell Road. The concept of the cemetery as a public park, which had been popularized by northern rural cemeteries, would take hold in earnest at Metairie. Carriage rides through the cemetery became part of a day trip to the West End or to the Halfway House. The cemetery was bordered on two sides by water – with Bayou Metairie to the south and the New Basin Canal to the east. As the cemetery was populated with high-style tombs, military tumuli, and grand society tombs, the recreational draw only increased. The founding of Metairie Cemetery was in itself the result of Reconstruction-era economic shifts. The cemetery later would fill with tombs and monuments reminiscent of the era. Confederate burial societies would erect grand tumuli in Metairie Cemetery; those who made their fortunes and gained political power in Reconstruction-era New Orleans would find their last rest there. In 1879, however, another cemetery would iterate an entirely different aspect of the period within its picket-fence boundaries. Less than a mile down Bayou Metairie, Holt Cemetery would be established. 1879: Holt Cemetery The cemeteries of Metairie Ridge each served a specific community: Cypress Grove served mostly northern-born Protestants, Odd Fellows Rest buried Odd Fellows, and so on. Cypress Grove Cemetery No. 2 and Charity Hospital Cemetery both served indigent dead and “strangers” (travelers or the newly-arrived). They were not by any means the only two cemeteries to serve as “potter’s fields.” In the nineteenth century, Protestant Girod Street cemetery held a section for indigent or epidemic burials; the city-owned cemeteries of Lafayette, Jefferson, and Carrollton also buried the indigent “at the expense of the city.[5]” Two additional cemeteries were operated by the City of New Orleans specifically as potter’s fields. They were Locust Grove No. 1 and No. 2. Located near LaSalle Street, at the center of what is now the Harmony Oaks housing complex, Locust Grove No. 1 was opened in 1859, with No. 2 opening in 1877. These cemeteries were located in the “back of town” near the St. Joseph Cemeteries and Lafayette Cemetery No. 2. This area was especially flood-prone, which vexed city health officials and caused much complaint about the condition of the Locust Grove Cemeteries. Furthermore, the city Board of Health often fretted about the transport of remains to this area, which was remote at the time. The state of public health in New Orleans was a topic of much debate in the 1870s. Many administrators of the Civil War Union occupation were proponents of the sanitary movement which valued clean streets, drainage, and sewage as public health concerns – a novel concept at the time. So it was that during Federal occupation special attention was paid to issues like standing water, disposal of slaughterhouse waste, and fresh air. The success of these policies is often measured in the fact that no epidemics took place during the occupation. The cause and effect are debated, but the result was the same. Some sanitarian notions persisted after the Civil War. The Slaughterhouse Case, a public health ordinance that became a landmark Supreme Court ruling, was one result of this new philosophy. However, care to restrict standing water and the breeding of mosquitoes slackened after 1865, and New Orleans saw a yellow fever epidemic in 1867. Eleven years later, the city would experience the worst yellow fever epidemic since 1853. As many as ten thousand people died in the New Orleans epidemic of 1878. The volume of indigent burials at Locust Grove Cemetery in 1878 was enough to exacerbate the cemetery’s already-poor reputation. The president of the Louisiana Board of Health at the time, Dr. Joseph Holt, a sanitarian in his own right, lambasted the condition of the cemetery.[6] In 1879, Locust Grove Cemetery No. 1 and 2 were closed and the City of New Orleans bought a small lot of land near City Park for a new municipal potter’s field. The cemetery was seen as an improvement for a number of reasons. Primarily, it was located on the raised land of Metairie Ridge, making in-ground burial more feasible. Board of Health records also show that the cemetery location was desirable for transportation purposes: remains could be transported down the “various shell roads” (the New Shell Road and the Bienville Shell Road) to the cemetery without too much exposure to primary thoroughfares. Finally, the cemetery was considered remote enough to minimize the chances of the cemetery itself breeding contagion or creating infectious “miasmas,” a concept that persisted into the late nineteenth century.[7] The cemetery was named after Dr. Joseph Holt (1838-1922), a nod to his pioneering studies in epidemiology and quarantine. It was not the first cemetery to be named after a person in New Orleans (McDonoghville Cemetery in Algiers has that claim), but it is certainly the only cemetery named after a person still living. Dr. Holt himself would be aware of his own namesake for forty-three years until his own death. Dr. Holt was buried in Greenwood Cemetery. In 1909, Holt Cemetery would be expanded toward St. Louis Street, nearly doubling its size. Enclosed with a simple picket fence and dominated by wooden markers, Holt succeeded Locust Grove as a cemetery utilized by African Americans, although not exclusively so. Over time, this cultural tie would make Holt Cemetery a place for the practice of African American burial traditions and a venue for folk memorial art. Although the cemetery ceased to be the municipal potter’s field in the 1960s, it remains in use by property owners to this day.[8]

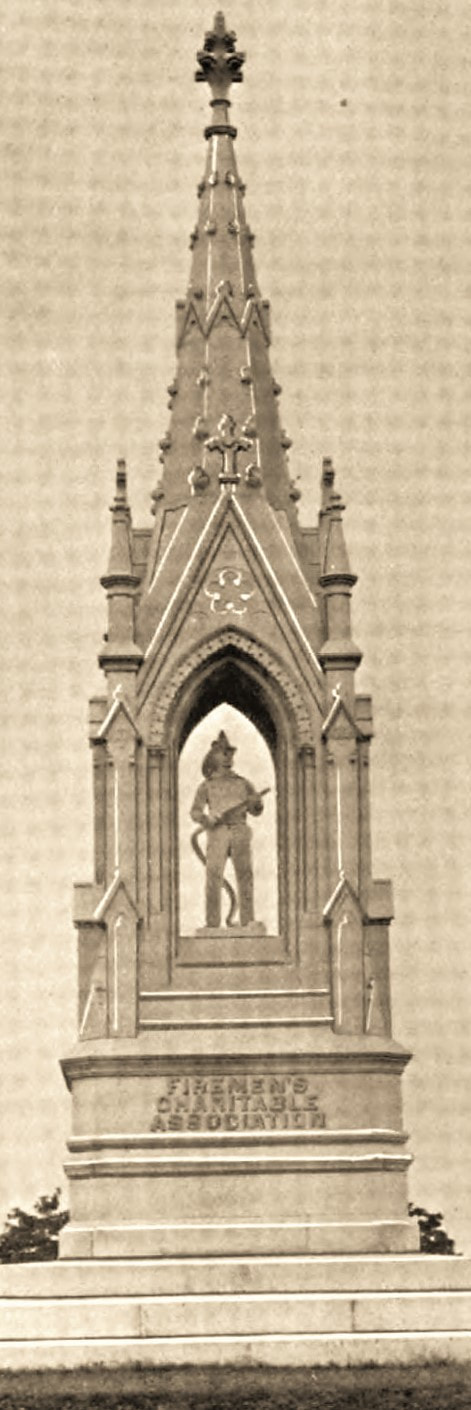

Greenwood had also acted as an extension of its sister cemetery, Cypress Grove, which was also owned by the Firemen’s Charitable Association (FCA). Much like Cypress Grove, the tumulus was a common burial style in Greenwood Cemetery. But for those who look upon Greenwood Cemetery today from the intersection of Canal Street and City Park Avenue, Greenwood would have been hardly recognizable in the early 1870s. As the bayou ran in front of the cemetery, none of the great monuments that the cemetery is known for had yet been built. This changed in 1874 with the Greenwood Cemetery Confederate monument. As mentioned in Part Three, the Ladies Benevolent Association purchased land at the front of Greenwood Cemetery, beside the Woodruff and Mcleod Monument. A monument was constructed there, designed by Benjamin Harrod of Metairie renown, and constructed by George Stroud, a stonecutter who worked prolifically in Greenwood and Cypress Grove cemeteries. At least one of the four busts mounted to the monument was carved by famed New Orleans sculptor Achille Perelli.[10] The Ladies Benevolent Association Confederate monument marks the mass grave of at least six hundred unidentified soldiers. It was the first of its kind in New Orleans, although the Washington Artillery, Army of Tennessee, Army of Northern Virginia, and the Soldier’s Home would establish similar burial sites for Confederate veterans. The Greenwood monument is the only one of its kind to exclusively memorialize those who died in action and without identification. Far on the southwestern boundary of Greenwood Cemetery and overlooking the New Basin Canal, the Confederate burial site would be among the tallest monuments in the landscape for a little over a decade. In 1887, however, the firemen of New Orleans who had owned and cultivated the cemetery for three decades would finally construct their own grand memorial. The FCA celebrated its fiftieth anniversary in 1885. The organization represented the volunteer firemen of New Orleans in both a professional and social capacity, and it functioned as New Orleans’ primary fire response. Dozens of fire companies dotted the city’s landscape, each company serving its neighborhood’s firefighting needs, and most companies provided burial in society tombs. The FCA also provided financial support for widows and orphans of firemen. For fifty years, the FCA had been the organization through which all fire companies functioned.[11]

Twenty years after the Hennessey monument, Albert Weiblen had capitalized on technological and infrastructure developments in the monument industry to such an extent that he purchase an entire Georgia marble quarry in 1911. In this same year, Weiblen was contracted to build the Elk’s Lodge tumulus in Greenwood Cemetery. The Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks (BPOE) has been present in New Orleans since the nineteenth century. Like many benevolent and fraternal organizations, the New Orleans Elks Lodge No. 30 sought a collective burial place to serve their members. While their aim to construct a society tomb was not unique, the Elks pursued their goal in a few unorthodox ways. For instance, the Elks raised the funds to construct the tomb by hosting a “burlesque circus” complete with elephants, acrobats, and a petting zoo of baby elks over Mardi Gras 1911. Elks members costumed as clowns and even travelled abroad to learn how to care for circus animals. Said one newspaper of the spectacle: “Quite a number of the antlered herd are taking corresponding lessons on how to manage elephants and camels.[13]” For Greenwood Cemetery and Albert Weiblen, however, the Elks defied a different kind of orthodoxy with their new tomb. The Elks lodge tomb would be a tumulus structure built at the very front of the cemetery, beside the Firemen’s monument. It is said that the Greenwood Cemetery property purchased by the Elks for this purpose is situated on the former bank of Bayou Metairie, which was in the process of being filled in by 1911. Weiblen, who would build dozens of remarkable tombs over the course of his career, as well as having a hand in the Stone Mountain monument in Georgia, contested the soggy location as incapable of supporting the tomb’s foundation. Yet the Elk’s Lodge tumulus was constructed despite these objections. Over time, some minor foundational issues have caused the tumulus to tilt toward Canal Street. The monumental mound remains a presiding element of the landscape today, with its bronze elk looking out over the intersection. Segregation in the Canal Street Cemeteries The period between 1873 and 1930 was also marked by Reconstruction and the later institution of Jim Crow laws – a period that began with the New Orleans Separate Cars Act in 1890, leading to Supreme Court case Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896. For the Canal Street cemeteries and New Orleans cemeteries as a whole, the institution of “separate but equal” services extended to memorialization and burial. Before the Civil War, many of the Canal Street cemeteries were de facto segregated – while burial of African Americans was not explicitly prohibited, such burials simply did not take place. The divide was mostly due to the fact that some cemeteries served primarily white religious communities such as German Lutherans or Irish Catholics. Cypress Grove Cemetery and Greenwood Cemetery were noted in 1881 as each having a section “set apart for colored persons.”[14] Jim Crow nonetheless made its mark on the Canal Street Cemeteries. While Holt Cemetery was not officially racially segregated, it remained the only cemetery in the area to primarily perform burial for African Americans. In some cases, the influence of racial restriction in cemeteries was more stark. In the winter of 1912, a recent burial in Odd Fellows Rest was found by the cemetery sexton to be that of an African American woman. Upon this discovery, the sexton exhumed the elderly woman’s grave and “dragged the casket containing the corpse out of the bounds of the cemetery. It was then conveyed to Cypress Grove.[15]” The incident called into question the understanding of segregation in cemeteries. The owner of the Odd Fellows plot, Mrs. Bowling S. Leathers, had purchased the lot that year for herself, her husband, and her “faithful old negro mammy.” However, the administration of Odd Fellows Rest insisted that the cemetery was for “white people of good character” only, and that Mrs. Leathers had misled the cemetery sexton as to the identity of the interred. The scant documentation of this incident highlights a conundrum for cemeteries that to this point were de facto segregated. The Times-Picayune reports that prior to the burial of Mrs. Leathers’ companion, cemetery sextons would only receive burial certificates from the city board of health after the interments were complete. As burial certificates would be the only official documentation noting the race of the deceased, these records suggest that in most cemeteries, enforcement of segregation would have been performed on a type of honor system, lest more disinterments take place. Mrs. Leathers sued the Odd Fellows for the incident, although the outcome of the suit is unclear. Ten years after the Odd Fellows controversy, Metairie Cemetery met its own segregation controversy. Long the designated burial ground of New Orleans’ political elite, in 1922 former Governor of Louisiana Pinckney Benton Stewart Pinchback was to be buried on its grounds.

Metairie Road, which paralleled Bayou Metairie, was expanded and would come to accommodate automobile traffic. Possibly in a response to the new traffic patterns, the entrance to Odd Fellows Rest was moved from Canal Street to the corner of Canal and what would become City Park Avenue. A large overarching parapet and awning was built at this corner of the cemetery – a project that necessitated removing a number of burial vaults. Beginning in the 1880s, the Firemen’s Charitable and Benevolent Association would advertise intermittently in newspapers that those with loved ones buried in Cypress Grove Cemetery No. 2 (also known as Charity Hospital Cemetery No. 2) should remove their kindred’s remains from the property. It is unclear when Cypress Grove No. 2 was officially closed, although it has been suggested that the cemetery had been inactive since the 1860s. By the 1920s, no monuments or traces of the cemetery remained. The property became a landfill.[16] The enterprising spirit of Albert Weiblen would make him an unparalleled success in New Orleans cemeteries. But Weiblen wasn’t alone in his path from local craft stonecutter to intrepid industrialist. By the 1920s, stonecutter Victor Huber was following a similar trajectory. In 1926, he opened his own showroom and workshop at 5055 Canal Street, beside Odd Fellows Rest. Like Weiblen, Huber would go on to orchestrate enormous changes in cemetery management and industry. Stonecutters like the Stewart brothers, who owned Acme Marble and Granite Company, and the Alfortish family, were also beginning to expand their aspirations in the cemeteries. The Halfway House, which had sat at the intersection of Bayou Metairie and the New Basin Canal since the 1840s, remained a place of diversion for day-trippers between the city and Lake Pontchartrain. By the 1920s, this clientele included riders of a streetcar that extended to the West End as well as automobile drivers along Metairie Road and the Shell Road. In this time, the Halfway House experienced a sort of renaissance. Jazz clubs in suburban neighborhoods saw their heyday in the 1920s, and the Halfway House, though sparsely furnished, was the home of the Halfway House Orchestra led by cornetist Albert “Abbie” Brunies. Multiple recordings of the Halfway House Orchestra are available even today, and the band is seen as a seminal element of 1920s New Orleans jazz.[17] From the 1860s to the 1930s, the intersection of Canal Street and City Park Avenue progressed from a quiet intersection of waterways and cemeteries to a burgeoning place of cemetery commerce, modern culture, and expanded architecture. By 1930, the beginnings of the traffic-choked cemetery intersections had come into view. The rest of the twentieth century would see even greater changes both within and outside of the cemetery walls. [1] Nikki Williams, “Racing and Slavery in Antebellum Louisiana, 1840-1865,” Louisiana Historical Association Conference, March 17, 2017, Shreveport, Louisiana.

[2] Henri A. Gandolfo, Metairie Cemetery: An Historical Memoir (New Orleans: Stewart Enterprises, 1981), 85-86. Gandolfo, who worked for Metairie Cemetery for most of the twentieth century, notes that another version of the story states Henry Howard was jilted for his association with the Radical Republican party. Gandolfo concludes, however, that no confirmation of any of these stories exist in either the racing association or the cemetery records. [3] “An Act (No. 60),” New Orleans Republican, March 26, 1873, 6; “Metairie Cemetery Association,” New Orleans Republican, November 9, 1873, 5. [4] Henri A. Gandolfo, 12-13. [5] Leonard Victor Huber and Guy F. Bernard, To Glorious Immortality: The Rise and Fall of the Girod Street Cemetery (New Orleans: Ablen Books, 1961), 78-80; Interment Records, Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, 1836-1968, New Orleans Public Library. [6] John H. Ellis, Yellow Fever and Public Health in the New South (University Press of Kentucky, 2015), 88, 100-103; Joseph Holt, M.D., “Appendix A: Taken from the Annual Report of the Board of Health for 1878, Locust Grove Cemetery,” The Monthly Review of Medicine and Pharmacy, Vol. II, No. 5 (May 1879), 74-75. [7] Leonard Victor Huber, et. Al, New Orleans Architecture, Vol. III: The Cemeteries, 60. [8] Peter B. Dedek, The Cemeteries of New Orleans: A Cultural History (Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 2017), 60-63. [9] “All Saint Day – The Living Remember the Dead,” New Orleans Republican, November 2, 1873, 1. [10] “Know Your City’s Public Monuments: Confederate Memorial,” Times-Picayune, February 7, 1926, 1-2. [11] Thomas O’Connor, editor, History of the Fire Department of New Orleans (New Orleans: FCA, 1890), 53; “Know Your City’s Public Monuments: Firemen,” Times-Picayune, April 11, 1926, 1. [12] “City Hall,” Daily Picayune, December 29, 1891, 5. [13] “Elks’ Circus to be a Feature During Carnival Week Here: Parade and Performances to be Filled with Features Farcy, Freakish and Funny,” Daily Picayune, January 15, 1911, 30; “Circus Catches: Pokorny’s Little Elks Arrive for Big Show,” Daily Picayune, February 17, 1911, 7. [14] George Washington Cable and George Edwin Waring, History and Present Condition of New Orleans, Louisiana and Report on the City of Austin, Texas (Washington, D.C.: US Government Printing Office, 1881), 72; Dedek, 131-133. [15] “Race Question in the Cemeteries: Mrs. Leathers Sues Odd Fellows for Ejecting Black Mammy’s Body,” Times-Picayune, December 4, 1912, 1. [16] Firemen’s Charitable Association Notice,” Daily Picayune, March 21, 1883, 5. [17] Samuel Charters, A Trumpet Around the Corner: The Story of New Orleans Jazz (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2008), 240-245.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

About the Author:Emily Ford owns and operates Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

- About

-

Restoration

- Services

-

Portfolio

>

- Turning Angel Statue, Natchez, MS

- Ledger Monument, Baton Rouge, LA

- Pyramid Statuary, New Orleans, LA

- Bronze and Granite Monument, Carville, LA

- Box Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Vernacular Concrete Monument, Pensacola, FL

- 1830s Family Tomb, Covington, LA

- 1850s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- 1880s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Headstone and Monument Restorations, Pensacola, FL

- Society Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Education

- Blog

- Contact

|

Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC is a preservation contractor in New Orleans, Louisiana, specializing in historic cemeteries, stone conservation, educational workshops and lectures. Oak and Laurel serves the region of the Southeastern US.

|

QUICK LINKS |

CONNECT |

Proudly powered by Weebly