|

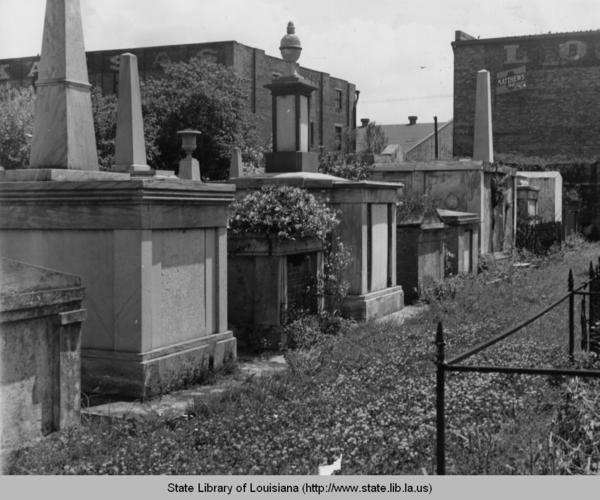

How were some of New Orleans' most beautiful tombs designed, and why? The architecture of New Orleans cemeteries is as diverse and varied as the neighborhoods in which the cemeteries are set. On one end of town, St. Vincent de Paul Cemetery grew from a peaceful field in the 1830s into a florid, tightly-packed garden cemetery full of Spanish and Italian inscriptions by the 1860s. Far uptown, the Americans built Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 from a below-ground graveyard into a little city of stone tombs in the same period. Between the two of them, the French-Creole cemeteries St. Louis No. 1 housed several generations of architecture within its walls decades before either Lafayette No. 1 nor St. Vincent de Paul were even conceived of.[1] Each tomb’s design in each cemetery is an adaptation of myriad influences, determined through the eye and imagination of mostly vernacular builders. Yet as is the case in all cemeteries, the appearance of the present is determined by what came before. In this blog post, we examine how a single influence gained a dual life in the form of the New Orleans sarcophagus tomb.

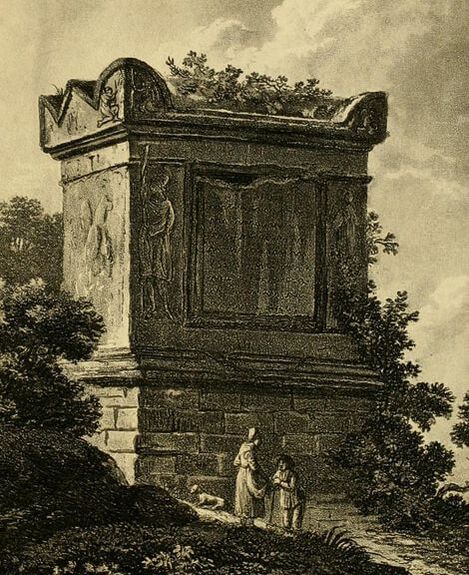

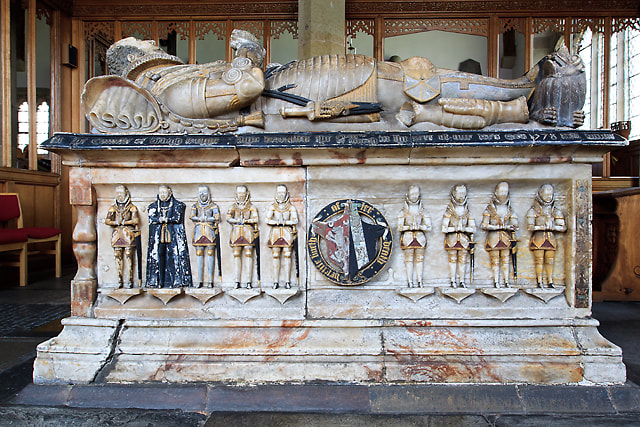

Classical Origins The word “sarcophagus” derives from the Greek words meaning “flesh” and “to eat,” translating roughly to “flesh-eating,” although there is debate on whether this name originates from folklore. In ancient Greece and Rome, the sarcophagus was a stone, clay, or metal vessel meant for the interment of a deceased body. Greco-Roman sarcophagi were richly adorned with carvings or paintings of the deceased’s life, mythology, or epic stories. In this way, they were meant for public display in burial grounds, funereal avenues, and even public places. They were a means through which the living interacted with the dead, and they had the aesthetics to prove it.

Rediscovering Classical Design A general shift in the way Western culture understood death took place toward the end of the 1700s. Before this time, the sanctity and identity of a deceased body was reserved mostly for the wealthy, powerful, or sainted. By 1790, cultural changes brought by scientific advancement, industrialization, urbanization, and the Enlightenment, gave birth to the modern concept of the cemetery. In France, this shift was noted by the closure of the Cimetière des Saints-Innocents (Cemetery of the Holy Innocents) and the opening of the cemeteries of Pere Lachaise and Montmartre. In France, the sarcophagus gained new life. The revival of the Classical Greco-Roman sarcophagus was spurred not only by a new desire to create beauty in cemetery landscapes. It was kindled by the rediscovery of its original form. In the late 18th and early 19th century, a renewed interest in Greek and Roman design led architects, artists, and historians back to their source. In the 1750s, the original Greek ornamental orders were rediscovered and published by two architects, one Scottish and one British. Half a century later, the Napoleonic Wars would both bring heightened understanding of Classical art on the continent and, conversely, stymie its spread to artists and architects outside France. These new discoveries led to the rise of Neoclassical architecture: an architectural period in which the designs and order of ancient Greece and Rome were repeated in public and private architecture on both sides of the Atlantic.[5]

On the other side of the country, New Orleans was even more newly American. Incorporated into the United States with the Louisiana Purchase in 1806 and ratified into statehood in 1812, Louisiana remained deeply French in its culture. It was the divide between French and American that would create two distinct sarcophagus tomb styles in the cities of the dead. Two Sides of Town New Orleans first above-ground cemetery was St. Louis Cemetery No. 1, established in 1789. It was a Catholic cemetery used by primarily French Creole New Orleanians (a small parcel at the rear was reserved for Protestant citizens). St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 replaced the St. Peter Street Cemetery, a below-ground graveyard which was quickly built-over. Yet St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 developed relatively haphazardly, with no specific plan or aisles, and was first populated by small tombs built in vernacular designs. By 1822, however, the layout of New Orleans cemeteries became more refined in two ways. First, the concepts of garden-type cemetery design arrived in New Orleans, and cemeteries were planned with aisles and even some vegetation (architectural historian Dell Upton has mused on the odd ways New Orleans both followed and did not follow the garden cemetery tradition). Second, the Catholics and Protestants established separate cemeteries. On one side of Canal Street, St. Louis Cemetery No. 2 was established. On the other side, the American side, the Protestant cemetery on Girod Street was built. Finally, in the 1830s, French architect Jacques Nicolas Bussiere de Pouilly (1804-1875) arrived in New Orleans. His work, based on pattern books from Pere Lachaise Cemetery in Paris, created in St. Louis Cemetery No. 2 a remarkable menagerie of tomb architecture.[7] This architecture was copied, adapted, and altered by vernacular builders for generations. From these origins came the sarcophagus tomb in two separate varieties – the French-Creole and the Anglo-American, primarily built between the 1840s and the 1860s. Unlike the “false” sarcophagi of European cemeteries and churches, the New Orleans sarcophagus tomb functions in the same manner as any other New Orleans tomb. It receives human remains through a frontal opening which holds one or two vaults. The remains are interred above ground within the walls of the tomb and enclosed by a stone (usually marble) tablet. In this way, the sarcophagus has travelled through the centuries to return to its original function. While similar in construction and often playing upon one another, specific traits can be noted in each variety of sarcophagus tomb, French-Creole and Anglo-American.

Compared to Anglo-American sarcophagus tombs, French-Creole sarcophagus tombs were Continental, somewhat exotic, and slightly more creative in the license taken with ornament, sculpture, and even the general silhouette the tomb cast on the cemetery. This could be cultural in nature, a result of the enormous body of influential work brought to New Orleans be de Pouilly, or simply a matter of aesthetics. A curious exception of this divide is the van Benthuysen tomb in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. Built around 1866 by Irish-born James Hagan, the tomb is a remarkably ornate structure filled with ornamental letter-work, interlocking geometric designs on the pediments of its cross-gable roof, and striking relief-carved inverted torches – all built by a non-French stonecutter in a primarily non-French cemetery.

While French-Creole sarcophagus tombs are found in the cemeteries that correspond to their Franco-Catholic community (mostly St. Louis Cemetery No. 2 and St. Louis Cemetery No. 3), Anglo-American sarcophagus tombs likewise followed their own ilk. They are found in Cypress Grove Cemetery, the first true garden-style rural cemetery in New Orleans. They are found in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 in their own variations. And they were well-represented in the Protestant Girod Street Cemetery, which was demolished in 1957.

If French-Creole sarcophagus tombs are denoted by their acroteria, Anglo-American sarcophagus tombs can be identified by their dentils. This may be a derivation from the dentil-rich Federalist architecture many of their creators may have known in the northern United States. The tendency of Anglo-American sarcophagus tombs to be both repeated and rich with dentils is beautifully highlighted by three near-identical tombs in three separate New Orleans cemeteries. Garner, Schinkel, and Walker-Behan A visitor to Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 will likely remember the Garner tomb. It stands on a quadruple lot at the end of an aisle and rises to nearly twenty feet tall. It is entirely clad in marble with ashlar-scored walls, a Classical cornice with dentils, and acanthus-leaf cornicework. Its roof is flat. Atop this roof rises a rectangular base ornamented with a floral swag and a draped urn sculpture. The tomb, most likely built around 1868, is signed by its carvers: Birchmeier & Simpson. Across town in St. Louis Cemetery No. 3, a visitor may round the corner to find themselves seeing double. The Schinkel tomb, likely built around 1869, is nearly identical. Its dentils, scored sides, and draped urn are exactly the same. The Schinkel tomb, however, bears a cross on its urn base and has the additional lovely ornamentation of sculptural panels on its primary façade. It’s signer: J. Frederick Birchmeier. Approximately two miles away, it was once possible to see a third sister in this group of triplets. The Walker-Behan tomb’s dentils, scored marble cladding, and draped urn sculpture once sat at the end of an aisle in Greenwood Cemetery. It is possible that it had the same builder as the Garner and Schinkel tombs – it was likely built in 1871. However, its collapse in recent years has made such a determination unlikely. These three tombs are a remarkable insight into the work and career of J. Frederick Birchmeier (1833-1889), but he has yet to be studied in-depth. In this context, the repeated function of the sarcophagus tomb, especially in its versatile Anglo-American variety, is well-highlighted in the case of these three. They cause one to wonder how many more were once present in the New Orleans landscape. Reading the New Orleans Cemetery Landscape The New Orleans sarcophagus tomb was most prominent in New Orleans cemeteries from the 1830s to around 1870. After the Civil War, new American architectural styles found their way into the cities of the dead: Gothic Revival, Italianate, and varieties of late-19th century Neoclassicism. The time of the sarcophagus had come and gone and left its mark. Like any study of larger elements in New Orleans cemetery landscapes, a closer look at the sarcophagus tomb brings to mind so many important undercurrents. The nature of the cemetery to be built upon, lot by lot, tomb by tomb, in each community in its own specific way means not only that each tomb is important to the cemetery’s history, but also that repeated motifs and styles like the sarcophagus tomb are significant as a group. The loss of Girod Street Cemetery was not only one massive loss of a single cemetery, but also an injury to the significance of cemeteries like Cypress Grove, in which similar architecture thrived in different ways. The loss of the Walker-Behan tomb is a loss to the Garner and Schinkel tombs because that significant aspect of their importance is wiped away. The landscape of each cemetery has its own language with myriad translations and a great deal of static that must be cleared away to properly understand them for what they are. In that spirit, we close with a gallery of so many other tombs that bear relationships to one another that may be overlooked:

[1] Special thanks to Jonathan Kewley for his advice regarding English cemetery architecture and helping to shape this article.

[2] Ann Merritt Masson, “The Mortuary Architecture of Jacques Nicolas Bussiere de Pouilly,” Tulane University Thesis, 1992, 48-49. [3] Maxine T. Wachenheim, “The Stylistic Development of Tombs in the Cemeteries of New Orleans,” Southwestern Louisiana Journal 3 (Fall 1959), 264-266. [4] Philippe Aries, The Hour of Our Death (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1981), 203-206. In his chapter “Tombs and Epitaphs,” Aries discusses the separation of the body from the tomb itself and its relationship to levels of anonymity in death. He points out a shift in which the “cultural unity” of the tomb and the body was destroyed by the thirteenth century and interprets this shift as a replacement of the sarcophagus with the coffin. [5] Frederick E. Winter, “The Study of Greek Architecture,” American Journal of Archaeology Vol. 88, No. 2 (Apr., 1984), 103. [6] David Charles Sloane, The Last Great Necessity: Cemeteries in American History (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991), 49. [7] Masson, 16. [8] “Rockland Lime,” Times-Picayune, November 22, 1866, 5.

2 Comments

8/5/2020 06:44:35 am

The perfect learning site, I am very happy to find here impressive architecture information, basically this rhinoarchschool is always updating us more models and effective models always.

Reply

9/8/2020 09:24:46 pm

Never knew the origin of the word "sarcophagus". Wow, scary!

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

About the Author:Emily Ford owns and operates Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

- About

-

Restoration

- Services

-

Portfolio

>

- Turning Angel Statue, Natchez, MS

- Ledger Monument, Baton Rouge, LA

- Pyramid Statuary, New Orleans, LA

- Bronze and Granite Monument, Carville, LA

- Box Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Vernacular Concrete Monument, Pensacola, FL

- 1830s Family Tomb, Covington, LA

- 1850s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- 1880s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Headstone and Monument Restorations, Pensacola, FL

- Society Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Education

- Blog

- Contact

|

Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC is a preservation contractor in New Orleans, Louisiana, specializing in historic cemeteries, stone conservation, educational workshops and lectures. Oak and Laurel serves the region of the Southeastern US.

|

QUICK LINKS |

CONNECT |

Proudly powered by Weebly