|

Kitsch decor, mid-century modern designs, and complex sales schemes... Community mausoleums – multi-vault, indoor structures that house dozens or hundreds of burials – are ubiquitous in the American cemetery landscape. Many that were constructed between the early 1960s and today remain in regular use, maintained by their owners and cherished by their stakeholders. Some have not fared so well. In this series, we examine the two periods of community mausoleum construction in the United States. In this part, we examine their mid-twentieth century popularity from approximately 1950 to 1980. In both parts, we will examine New Orleans’ role in the community mausoleum movement. (You can find Part One here.) By 1950, the concept of the community mausoleum was forty years old. But the American public itself had seen several generations, a Great Depression, and two World Wars go by. In a way, the original allure of the community mausoleum had become part of American culture itself – the advertising had worked. A culture that forty years previous had held funerals in the home and generally eschewed embalming now understood the funeral home to be part of “tradition” and embalming to be essential to sanitation. But the world had also changed. The gargantuan technological leaps made to fight World War II had come home in the form of stronger concrete, bigger buildings, and an age of unparalleled American prosperity. Where before the community mausoleum was marketed as, in part, affordable, the appeal of affordability was no longer as necessary. The public wanted a new modernity to separate from the modernity understood by their grandparents. And they wanted it to be maintenance free, clean, and without the cobwebs of yesteryear. The new, midcentury modern community mausoleums would deliver. As discussed in Part One, New Orleans cemeteries were overwhelmingly uninvolved with the early twentieth century community mausoleum. With the notable exception of Hope Mausoleum, none were built in the New Orleans area. The midcentury mausoleum would be much more at home within the Crescent City, with more than a dozen constructed. The influx of community mausoleums was timely in that it coincided with shifts in cemetery management as a whole. The Modern Modern Community Mausoleum Although the community mausoleum movement is understood to have two distinct periods of development (before and after World War II, essentially), the construction of community mausoleums nationwide never truly ceased. In fact, the Michigan architect firm Harley Ellis Devereaux notes in their history that community mausoleum projects helped the firm survive the Depression.[1] Firm principle Alvin Harley (1884-1976) designed the mausoleum at White Chapel Memorial Park in Troy, Michigan in 1934. He himself would later be buried there. After World War II, Harley’s firm would construct some of the best-known midcentury mausoleums, including Queen of Heaven Mausoleum in Chicago (1956-1964), Resurrection Mausoleum in Justice, Illinois (1969), the Mausoleum at Woodlawn Cemetery in Detroit, and Mausoleum of the Saints at Resurrection Cemetery, Mount Clemens, Michigan.[2] Queen of Heaven is the world’s largest Catholic mausoleum, and Resurrection Mausoleum is home to the world’s largest stained glass window. Harley Ellis Devereaux’s midcentury mausoleum work was emblematic of the time: opulent, intensely decorated, spangled with stained glass. These were not neoclassical mausoleums meant to invoke the timelessness of Halicarnassus. They were meant to imbue the cemetery with the new hopefulness of the modern age. The change in mausoleum design and message was simply part of much larger cultural changes in the mid-twentieth century. It has already been noted that the technological advancements of World War II came home to change daily American life. Everyday items like ballpoint pens, modern printing, computer technology and super glue were derived from military invention. This was true for building trades as well, most notably with the rise of high-compression ready-mixed concrete. Larger, more complex buildings were easier and cheaper to make. All of this combined with the prosperity of peacetime made Americans feel optimistic, forward-looking, and less inclined to connect with the sober realities of death.

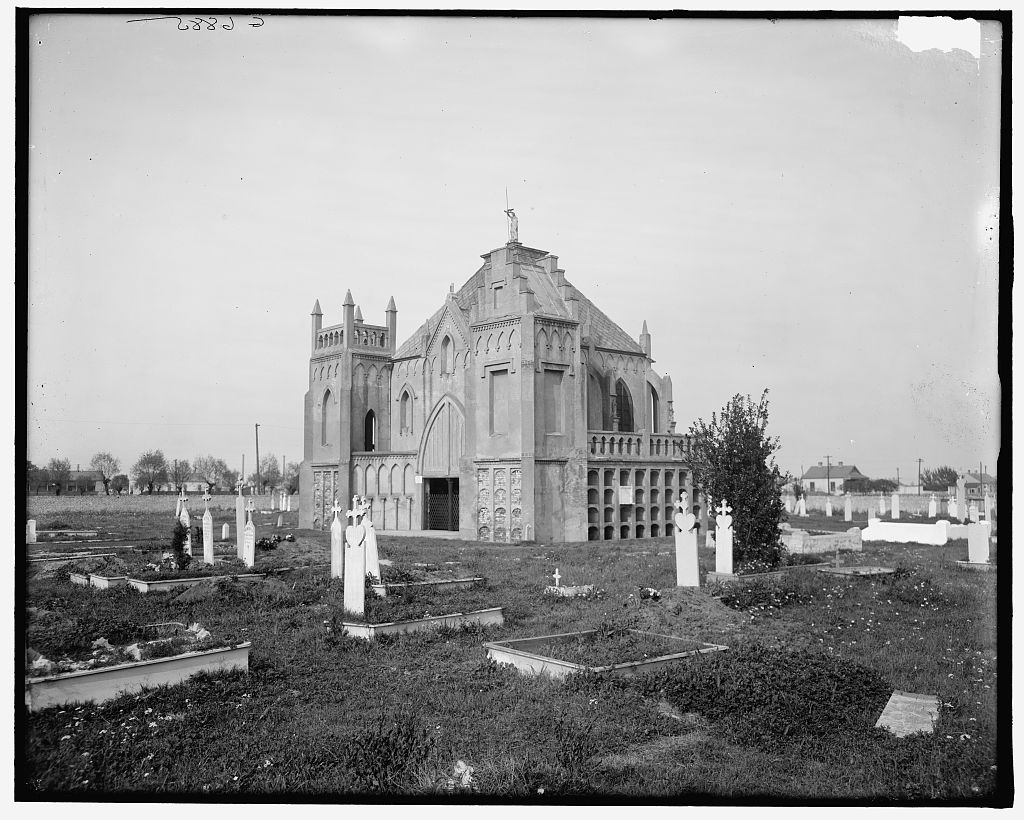

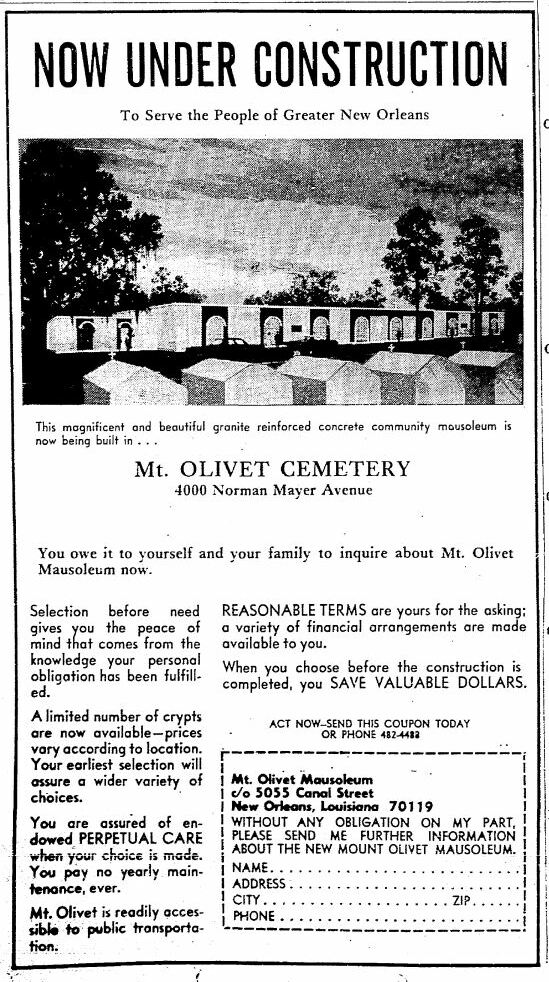

After the 1950s, the funerary industry elevated its efforts to build new revenue streams. From these operational demands came innovations like perpetual care, cemetery/funeral home collaborations, monument companies taking over the management of cemeteries, and, of course, the community mausoleum. The community mausoleum allowed a cemetery to redevelop a small area of its property to establish dozens, hundreds, or thousands of sellable units. This expansion reached even the halls of state legislatures. Starting in the 1950s, state cemetery and funeral director associations often participated in the crafting of legislature to regulate their own industry, which allowed mainstream cemeteries and funeral homes to curb bad actors as well as their own competition. Unlike the pre-WWII community mausoleum movement in which speculators were often pitted against older groups like the monument industry, the two joined forces. During this time, cemeteries shifted from the hyper-local management of sextons and churches to the management of conglomerates. These conglomerates performed the roles of both cemetery association and community mausoleum company. New Orleans was by no means an exception to this trend. Postwar Community Mausoleums in New Orleans Hope Mausoleum, which was built in 1930, was New Orleans first community mausoleum. For nearly thirty years, it was the city’s only community mausoleum. Like so many other mausoleums, Hope was constructed in part as a way to generate revenue from historic St. John Cemetery once it was taken over by the Huber family. In this regard it is surprising that it took so long for the rest of New Orleans cemeteries to follow suit.[5] After World War II, however, the cities of the dead did join the era of community mausoleums. Metairie Cemetery would build its first community mausoleum in 1958. In 1964, Catholic cemeteries which had to this point been managed by their respective parishes were conglomerated into one managerial entity: New Orleans Archdiocesan Cemeteries. The reorganization would galvanize the need for new, sellable space in these historic cemeteries. These needs were met in part by an energetic community mausoleum building campaign through the 1970s. In 1966, privately-owned St. Vincent de Paul Cemetery would develop an enormous, block-long community mausoleum. The Firemen’s Charitable Benevolent Association would build Greenwood Mausoleum in 1970. Historically segregated cemeteries Mount Olivet and Providence Memorial Park saw community mausoleums built in the 1970s. But before all of these mausoleums were constructed in historic cemeteries, New Orleans would see the concept played out in bright, modern fashion with Lake Lawn Mausoleum. Lake Lawn Park Mausoleum By the early 1950s, the Stewart family was at the forefront of the New Orleans monument industry. Albert Stewart and his sons Charles and Frank, Sr. had expanded from their neighborhood marble yard into a national monument agency.[6] Evolving their trade in a similar manner to their contemporary Albert Weiblen, they had proved to be ahead of their time. In the early 1900s they had become the first of their trade to outrightly own a cemetery when they acquired St. Vincent de Paul Cemetery on Louisa Street. In the mid-1950s, Albert Weiblen purchased Metairie Cemetery, the crown jewel of New Orleans cemeteries. Looking beyond the business generated at St. Vincent de Paul, the Stewarts conceptualized an entirely new cemetery and planned to build it directly beside Metairie Cemetery. The central feature of the cemetery would be a mausoleum like nothing before seen by New Orleaneans. It would be ultra-modern, exuding qualities of permanence and style. They broke ground around 1952. Newspaper advertisements pressed the technological advancement and construction cost of Lake Lawn Mausoleum: Engineered reinforced concrete piling numbering one thousand and sixty piles will be installed to assure a permanent structure. Concrete piling is being used irrespective of the fact that the cost is double of the usual wood piling because this building, as well as future additions, is designed to withstand the ages. The exterior of this massive building will be of granite, the well-known natural stone that weathers time, such as was used in the famous pyramids of Egypt constructed over five thousand years ago.[7] Lake Lawn Mausoleum, its first phase completed in 1957, was designed by Jules K. de la Vergue and John M. Lachin. Like most community mausoleums, it has long, horizontal massing with modern stained-glass windows. The entryway of the mausoleum is set back and punctuated by a tall granite-and-glass tower with floor-to-ceiling glass windows. Its appearance is exceptionally modern, in contrast with the traditional historic cemetery landscape. Lake Lawn suited the cultural attitudes of the day. It is not a coincidence that Lake Lawn Mausoleum was completed the same year that Girod Street Cemetery was demolished. In fact, Lake Lawn competed for the contract to relocate the remains of white people from the demolished cemetery (Hope Mausoleum won that contract). Girod Street Cemetery was demolished because it was in the way of a New Urbanist civic complex. The distain of the old and appreciation with the new fits well with the construction of Lake Lawn Mausoleum – Mayor deLesseps “Chep” Morrison himself relocated the remains of his family from Girod Street Cemetery to Lake Lawn Mausoleum. Metairie Mausoleum By the time Lake Lawn Park and Mausoleum was completed, Albert Weiblen had passed away, leaving his widow Norma to manage Metairie Cemetery. There had already been some competition between the two neighboring cemeteries (most notably a clash over the burial of Chep Morrison himself), and Metairie Cemetery needed to meet that competition. In the 1950s, Metairie Cemetery developed a section of lots on the southwestern portion of the property, near what is known as “Millionaire’s Row” and the Army of Northern Virginia tumulus. This area would become Metairie Mausoleum. Metairie Mausoleum was the cemetery’s first community mausoleum, and it oddly had more in common with pre-World War II mausoleums than its late 1950s contemporaries. Its design is neatly Neoclassical, with stylized columns and an arched entryway leading to its outdoor hallways. If the mausoleum was meant to compete with Lake Lawn Park, it was far too simple and did not have enough burial space to do so meaningfully. Around the same time, and even more unusual community mausoleum was built in Metairie Cemetery. Or rather it was not even built but forged out of another tomb. One of the dozen Italian society tombs present along Avenue B was halfway demolished in the mid-1950s by Victor Huber (of Hope Mausoleum). The historic structure which once had a dome and lovely turrets (it’s unclear to which society it belonged) was stripped of its historic ornament and re-covered in Portland cement concrete to create a new-looking Art Deco mausoleum. It remains on Italian Row today and is listed on maps as “Excelsior Mausoleum.[8]” The Catholic Cemeteries and their Community Mausoleums Metairie Cemetery was in no way alone in its efforts to demolish historic structures to make way for new sellable space. The formation of the New Orleans Archdiocesan Cemeteries organization in the mid-1960s heralded a new age for all Catholic cemeteries including St. Patrick, St. Joseph, St. Roch, and St. Louis. All of these cemeteries had previously been managed by sextons, single individuals who cared for their respective one or two cemeteries and sold properties as needed. This model had long been replaced with a commodity/property sales approach in cemeteries outside New Orleans. The first director of the New Orleans Archdiocesan Cemeteries commission was Msgr. Raymond Wegmann, who outlined the new approach in 1967: “We were behind the times in the management of our cemeteries. Other dioceses consolidated their cemeteries under one office years ago.[9]” In this same article, Msgr. Wegmann and lay director Frank Rome laid out the necessity for the construction of community mausoleums, as it makes “the maximum use of the remaining land in the cemeteries, of which there is not much… [a] proposed mausoleum will accommodate about 685 [burials] in a plot space that would normally accommodate only 100.[10]” During this same time period, the Archdiocesan Cemeteries actively searched for lot owners, specifically in the St. Roch and St. Patrick cemeteries, where many burials were below ground. Frank Rome notes that without the presence of tomb owners, properties would “eventually” have to be demolished. It appears that this was the case for construction of community mausoleums in both St. Patrick Cemetery No. 1 and St. Roch Cemetery No. 2. During this time, all of the community mausoleums in Catholic cemeteries were built by Acme Marble and Granite Company, owned by the Stewart family.[11] St. Patrick Cemetery No. 1, established in 1840, was for most of its history a predominantly below-ground cemetery dotted with wooden headboards.[12] In 1891, a Calvary comprised of bronze statues of the crucified Christ, Mary, John the Baptist, and Mary Magdalene was erected in the rear of the cemetery. Although the St. Patrick Cemeteries tended not to receive the kind of attention other New Orleans cemeteries did, travel brochures from the turn of the century noted the Calvary as a local attraction.[13] In 1973, the Calvary was removed to make way for a new community mausoleum. In keeping with the midcentury mausoleum advertising, director Msgr. Wegmann stated that the mausoleum would be “modern” and fill a “very pressing need.” Continued Wegmann, “the cherished Calvary Crucifixion Group, sadly, had worn with time, but we are proud and happy to announce its replacement by a magnificent new group.[14]” It is unclear where the original 1891 Calvary group was moved to. Calvary Mausoleum indeed does have a modern Carrara marble relief carving of a Calvary group mounted to its primary façade, as well as a stained glass “Mater Dolorosa” or “Sorrowful Mother” mosaic feature in the outdoor community mausoleum. St. Roch Cemetery No. 2 was re-developed in the mid-1950s when St. Michael’s Chapel (constructed 1893) was renovated to accommodate mausoleum-style burials. The Our Lady Queen of Angels Mausoleum was constructed in 1967, and five other community mausoleums would follow, including St. Joseph Garden Mausoleum, which was finished in the past few years. While St. Roch Cemetery No. 1 retains some historic material previous to the 1920s, the wooden markers and belowground burials of St. Roch Cemetery No. 2 were erased by community mausoleum development and construction of “community tombs,” making the space an entirely new landscape.

Mount Olivet Cemetery was by no means the only exclusively African American cemetery in the New Orleans area to join the community mausoleum movement. In 1953, Providence Memorial Park opened along Airline Highway in Metairie. It was not a coincidence that Providence Memorial Park was located so near to Garden of Memories Memorial Park – it was intended to provide the “garden style” cemetery model to African American customers, and was advertised as such.[18] It appears that Providence Memorial Park did not join the community mausoleum movement until at least the 1970s, with one small community mausoleum to the rear of the property. Since the 1980s, however, two very large multi-vault community mausolea were constructed, one of which provides the cemetery’s primary street exposure. Community Mausoleums Today The New Orleans community mausoleum boom stretched into the 1990s, most of which were constructed by Acme Marble and Granite Company. Although an exact count isn’t readily available, Acme Marble and Granite constructed at least 500 community mausoleums in 38 states as well as Canada.[19] In 2013, Stewart Enterprises was purchased by Service Corporation International (SCI). In 1971, Hope Mausoleum established the first crematorium in Louisiana. Today, as more than half of Americans choose cremation (up from 5% in 1972), many already-built community mausoleums are adapted to accommodate columbaria or cremation niches. Among these are Providence Memorial Park Mausoleum, Greenwood Mausoleum, and Lake Lawn Mausoleum. New Orleans Archdiocesan Cemeteries have built columbaria in several of their cemeteries, free-standing from community mausoleums. Elsewhere in the United States, community mausoleums continue to be built in one town as another town may struggle to preserve an historic mausoleum. Most that fall to decay are those constructed prior to 1945 by speculating mausoleum companies – in these cases, ownership of the building itself can be unclear and thus so is responsibility for maintenance. In some rare cases, mausoleums are saved from the brink of ruin and redeveloped. The enormity of their size and complication of their construction can create daunting issues, particularly in regard to the care of the remains within. Community mausoleums began more than a century ago as a response to changing death culture. Over time, as the American attitude around death changed, community mausoleums changed with them. It is safe to presume that, despite the tragic fall of some historic structures to neglect or mismanagement, the community mausoleum will remain a part of cemetery landscapes for years to come. [1] Harley Ellis Devereaux Corporation, “100 Years, 1908-2008, A centennial of superior quality, unequaled service, and constant innovation,” online resource, 13-15.

[2] Like many modern cemeteries, Resurrection Cemetery has continued to build and add new mausoleums each decade or so. [3] “The Furor Over Funerals: Why the Cry of Scandal?” The Kiplinger Magazine, Vol. 17, No. 11 (November 1963), 7-12; Jessica Mitford, The American Way of Death (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1963), 235-236. [4] Mitford, 101. [5] Huber et. Al., New Orleans Architecture, Vol. III: The Cemeteries (Gretna: Pelican Publishing, 1974), 48. [6] Henri Gandolfo, Metairie Cemetery: An Historical Memoir (Stewart Enterprises, 1981), 95. [7] “Lake Lawn Park and Mausoleum,” Times-Picayune, October 31, 1952, 11. Ironically, the Egyptian pyramids are not made from granite, but instead are faced with limestone. [8] Henri Gandolfo, 112. [9] Florence Herman, “Cemetery Can be Solace to Living,” New Orleans Clarion Herald Vol. 5, No. 35 (Oct. 1967), 1. [10] Ibid. [11] Ibid. [12] “A Cemetery Blaze,” Times-Picayune, February 27, 1905, 11. [13] Huber et. Al., 33; The Picayune’s Guide to New Orleans (New Orleans: Times Picayune, 1904), 152. [14] “Burial Vaults Will Be Built,” Times-Picayune, February 24, 1973, 16. [15] “Gretna Grants 139 Permits,” New Orleans Item, September 9, 1948, 25; “Begin Health Menace Probe of Cemetery,” New Orleans States, October 4, 1957, 26; Times-Picayune, October 16, 1917. [16] “Gentilly Mausoleum to be Expanded,” Times-Picayune, December 20, 1986, 7. [17] “Now Under Construction,” Times-Picayune, October 10, 1971, Sec. 1, Page 22; “Three Corridors Complete…” Times-Picayune, October29, 1972, Sec. 1, Page 27. [18] “Announcing Providence Memorial Park, the Most Beautiful Exclusively Negro Cemetery in the South,” Times-Picayune, August 15, 1954, 10. [19] “Gentilly Mausoleum to be Expanded,” Times-Picayune, October 20, 1986, 7.

1 Comment

7/16/2024 06:49:11 am

The evolution of community mausoleums reflects changes in societal attitudes towards remembrance. What are the most significant architectural or design trends in modern mausoleums?

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

About the Author:Emily Ford owns and operates Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

- About

-

Restoration

- Services

-

Portfolio

>

- Turning Angel Statue, Natchez, MS

- Ledger Monument, Baton Rouge, LA

- Pyramid Statuary, New Orleans, LA

- Bronze and Granite Monument, Carville, LA

- Box Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Vernacular Concrete Monument, Pensacola, FL

- 1830s Family Tomb, Covington, LA

- 1850s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- 1880s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Headstone and Monument Restorations, Pensacola, FL

- Society Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Education

- Blog

- Contact

|

Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC is a preservation contractor in New Orleans, Louisiana, specializing in historic cemeteries, stone conservation, educational workshops and lectures. Oak and Laurel serves the region of the Southeastern US.

|

QUICK LINKS |

CONNECT |

Proudly powered by Weebly