|

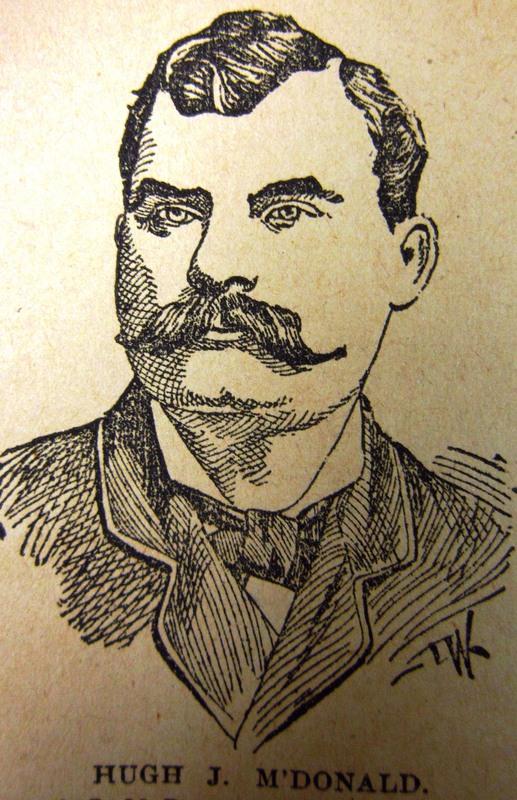

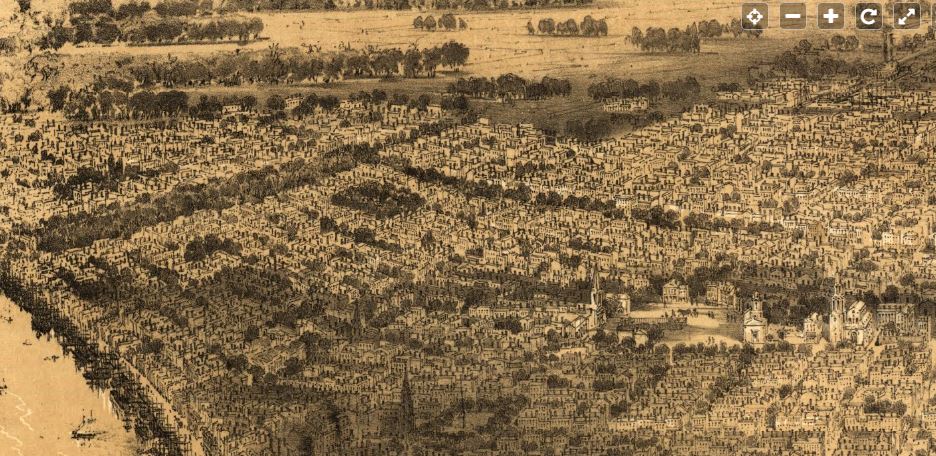

The life and times of a New Orleans cemetery caretaker. Adapted from Emily Ford, “The Stonecutters and Tomb Builders of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, New Orleans, Louisiana,” Master’s Thesis, Clemson University, 2013. New Orleans cemeteries are centers of its heritage, not only as the final resting place for great historical figures, but also as places where historic craftwork endures in brick and stone. Within the avenues and aisles of the Saint Louis Cemeteries, Lafayette Cemeteries, St. Roch, St. Vincent de Paul, and others, there are hundreds of stonecutters, tomb builders, and vernacular architects for whom, it seems, only a carved signature remains. In Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, for example, nearly two dozen tombs are signed by one such craftsman: H.J. McDonald.[1] Hugh Joseph McDonald (1848 – 1895) was a stonecutter and tomb builder who spent most of his life within blocks of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. He was a Civil War veteran, a state representative, local politician, and skilled craftsman. He apprenticed with stonecutters and tomb builders who carried on a long tradition of stewardship to New Orleans cemeteries and, in turn, he mentored those who took his place. He was active during a time of great technological, stylistic, and material changes to the crafts of masonry and monument carving. As an artisan and as a member of his community, he earned his name, written in stone, among the tombs of New Orleans. Unlike some better-known New Orleans craftsmen, McDonald was a man without French or Creole background. He was instead a member of a large and culturally influential community of Irish immigrants located in the Fourth District, the former suburb of Lafayette – today comprised of portions of the Garden District, Irish Channel, and Central City neighborhoods. In 1852, the same year Lafayette was absorbed into the City of New Orleans, Hugh J. McDonald arrived in Louisiana, a four year old boy disembarking with his parents and siblings after a long voyage from County Antrim, Ireland.[2] Like thousands of others arriving in the United States in the 1840s and 1850s, the McDonalds were fleeing famine in their homeland.[3] Hugh McDonald spent his early life in Pass Christian, Mississippi. At the start of the Civil War, he was only thirteen years old, yet both newspaper and military documentation show that he joined the Confederate Fourth Louisiana Regiment in 1861. Stated his obituary: …the boy, fascinated with the prospect of military glory, ran away with the regiment when it started for the front. He was too small to carry the regulation musket, and so a gun was fabricated for him in Paris and brought over by blockade runners. On being released from the hospital [after being wounded at the Battle of Shiloh], he entered General [James] Longstreet’s corps and served in Virginia, being present at the battle of Chancellorsville, and on the scene when General Stonewall Jackson was killed. He was captured and was in prison at Camp Douglas for three months. After Treaty of Appomattox, McDonald returned to Pass Christian briefly, and soon afterward moved to New Orleans where he lived on Melpomene Street, near what is now South Robertson. He became active in the local Democratic Party, a function which would lead to larger political roles and eventually a state congressional seat in the 1870s. He also entered the stonecutting trade at this time, beginning as an apprentice to J. Frederick Birchmeier, a sexton and stonecutter whose work is prominent within the walls of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1.[4] In 1872, he married Louisiana native Mary Jane Condon.[5] McDonald’s ties to the larger community of stonecutters and tomb builders in the Fourth District stretched far beyond his employment with Birchmeier. His place within the geography of this craft alone bears noting. By 1870, he moved to 193 Washington Avenue, an address located across from Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. He lived next door from Birchmeier’s home and marble yard. Across Prytania Street from Birchmeier and McDonald was the marble yard of James Hagan (in the lot that is today the Rink shopping center). Only a few blocks down Washington Avenue, near Lafayette Cemetery No. 2, other members of this community maintained their businesses: John Alfortish, the first in a long line of Alfortish marble cutters, lived at what is today Danneel Street (then Laurent Street), John Hagan, brother of James, and Mathias Huber, the first sexton of Saint Joseph’s Cemetery all lived and worked side-by-side on Washington Avenue. Hugh J. McDonald would be involved personally and professionally with all of these men.[6] In 1875, McDonald became foreman of J. Frederick Birchmeier’s marble shop. In this capacity, he mentored a young stonecutter named Gottlieb Huber, son of Mathias Huber. Three years later, he would depart from Birchmeier’s employ and begin his own business, located between South Rampart and South Basin Streets on Washington (today these streets are known as Danneel and Saratoga, respectively). He also moved his residence to this area, near Lafayette Cemetery No. 2 and St. Joseph’s Cemetery. This year, 1878, was a tragic year for both McDonald and the city of New Orleans as a whole. The yellow fever epidemic of 1878 claimed two of McDonalds’ sons, Robbie Gibson (two years old) and James Lee (seven years old). McDonald’s other two sons, Hugh Jr. and Edward Leo, survived into adulthood. The epidemic of 1878, however, would prove to be a catalyst for the methods and materials used by McDonald and his contemporaries for building tombs and carving closure tablets. The greater need for burial space and the close professional relationships between craftsmen like McDonald, Birchmeier, Huber, Hagan, Joseph F. Callico and others, led these men to construct nearly identical tombs, developing models from which each man borrowed. As all of the above listed craftsmen would become sextons of Lafayette Cemeteries No. 1 and 2, their position would also allow them to purchase adjoining lots and develop them with numerous identical tombs, a phenomenon that is visible in the cemeteries even today. McDonald’s influence over the landscape of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, in particular, extended beyond that of his colleagues due to his position as a Louisiana state representative. In addition to serving with James Hagan (then a state senator) on the committee to restore the old Louisiana State Capitol building in Baton Rouge, McDonald also chaired the Louisiana House special committee on cemeteries. [7] In 1880, his committee report stated the condition of the St. Louis and Lafayette Cemeteries as “proper,” although he strongly recommended the Protestant Cemetery on Girod Street be closed for sanitary purposes. He further requested that no further interments be made in the wall vaults of any of the St. Louis or Lafayette Cemeteries. Available documentation concerning the wall vaults in Lafayette No. 1 suggests that this request was likely granted, and the use of wall vaults was prohibited after 1880.[8]

Charles A. Orleans, a well-known New Orleans stonecutter, acted as a pallbearer. J. Frederick Birchmeier had died in 1889, but it is logical to assume that James Hagan and Gottlieb Huber would have attended. Both the Firemen’s Charitable Association and the Pike Benevolent Association were present in rank. It is unclear where Hugh McDonald was originally buried, as newspapers reported both Greenwood and St. Joseph Cemetery No. 1 as the place of his interment. His remains today, however, are interred in a tomb at Metairie Cemetery with those of his sons and his wife, likely constructed in the decades after his death.

[1] Based on a combination of the 1981 Historic New Orleans Collection Survey of Historic New Orleans Cemeteries (MSS 360) and a 2012 assessment of all signed work in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, comprising 291 individual signed tombs and other elements.

[2] “Hugh J. McDonald: A Popular Politician and Veteran Soldier Passes Away,” Daily Picayune, October 22, 1895, 3; State of Louisiana, Secretary of State, Division of Archives, Records Management, and History, Orleans Parish Death Indices 1877-1895, Vol. 109, 777. County Antrim is located on the northern coast of what is today Northern Ireland. [3] State of Louisiana, Secretary of State, Division of Archives, Records Management, and History, Vital Records Indices, 1877-1895, Vol. 92, 540. [4] As of 2013, more than eighty individual lots bear the signature of J. Frederick Birchmeier. [5] United States of America, Bureau of the Census, Thirteenth Census of the United States, 1910, New Orleans Ward 17 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration), Roll T624-525, page 17B. [6] Grahams Crescent City Directory for 1867 (New Orleans: A. Graham, 1866), 99, 224; Soards’ New Orleans City Directory for 1875 (New Orleans: Soards Publishers, 1875), 457; Soards’ New Orleans Directory for 1876 (New Orleans: Soards Publishing Company, 1876), 453; Soards’ New Orleans Directory for 1877 (New Orleans: L. Soards & Co., 1877), 460; Edwards’ Annual Directory…in the City of New Orleans, for 1872 (New Orleans: Southern Publishing Company, 1872), 62, 289. [7] “Legislative Aspirants,” Daily Picayune, October 31, 1881, page 2; Louisiana State House of Representatives, Official Journal of the Proceedings of the House of Representatives of the State of Louisiana at the Regular Session, Begun and Held at New Orleans, January 12, 1880 (New Orleans: The New Orleans Democrat Office, 1880), 182-183. [8] Williams Research Center, Historic New Orleans Collection, “Miscellaneous Correspondence and Records Pertinent to Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, Microfilm Reels 87-37-L. Page 124 in untitled sexton’s ledger book. The latest sale of a wall vault by a sexton in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 dated to 1880. The subsequent record documenting the removal of remains from the Sixth Street wall vaults appears to be Vault No. 3, Peter Hanson, died April 25, 1876. [9] Soards’ New Orleans Directory for 1886 (New Orleans: L. Soards & Co. Printers, 1886), 488; Soards’ New Orleans Directory for 1887 (New Orleans: L. Soards & Co. Publishers, 1887), 516; Soards’ New Orleans Directory for 1893 (New Orleans: L. Soards Publisher, 1893), 506; Soards’ New Orleans Directory for 1894 (New Orleans: L. Soards Publishing, 1894), 508; Soards’ New Orleans Directory for 1895, Vol. XXII (New Orleans: L. Soards, Publisher 1895), 534. [10] “Hugh J. McDonald: A Popular Politician and Veteran Soldier Passes Away,” Daily Picayune, October, 22, 1895, page 3. [11] Daily Picayune, October 27, 1895, page 6.

2 Comments

Michael McDonald Sr.

5/25/2020 02:54:16 pm

This is a great history of my Great Grand Father and my family.

Reply

Judy Balser

4/26/2022 06:45:52 pm

Mentions my great-great grandfather Mathias Huber, who was the first sexton of St. Joseph Cemetery.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

About the Author:Emily Ford owns and operates Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

- About

-

Restoration

- Services

-

Portfolio

>

- Turning Angel Statue, Natchez, MS

- Ledger Monument, Baton Rouge, LA

- Pyramid Statuary, New Orleans, LA

- Bronze and Granite Monument, Carville, LA

- Box Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Vernacular Concrete Monument, Pensacola, FL

- 1830s Family Tomb, Covington, LA

- 1850s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- 1880s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Headstone and Monument Restorations, Pensacola, FL

- Society Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Education

- Blog

- Contact

|

Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC is a preservation contractor in New Orleans, Louisiana, specializing in historic cemeteries, stone conservation, educational workshops and lectures. Oak and Laurel serves the region of the Southeastern US.

|

QUICK LINKS |

CONNECT |

Proudly powered by Weebly