|

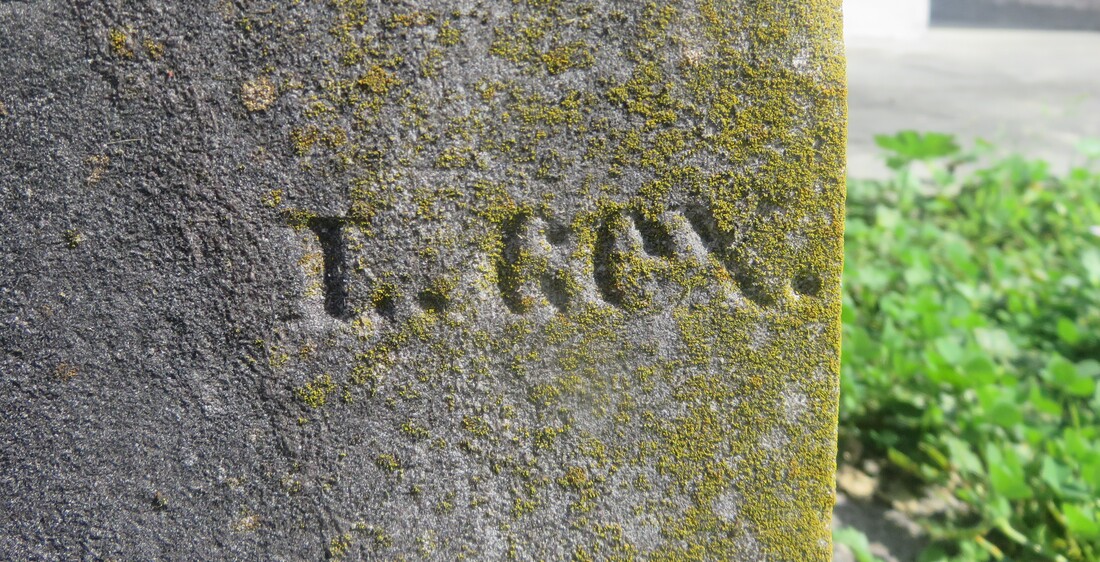

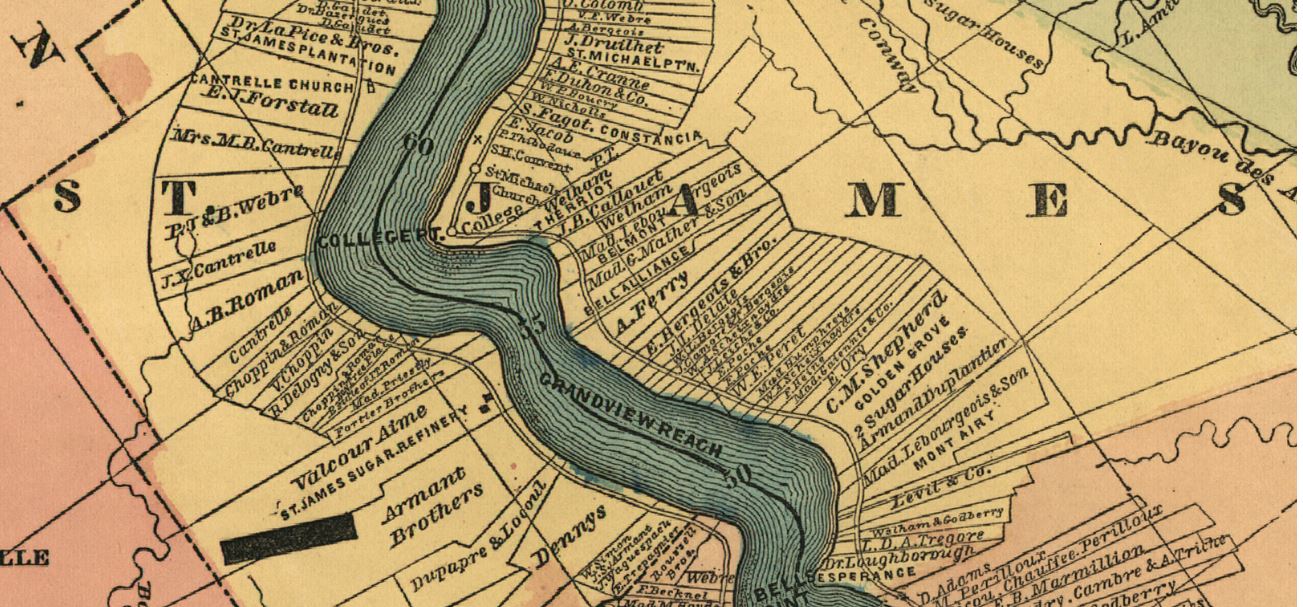

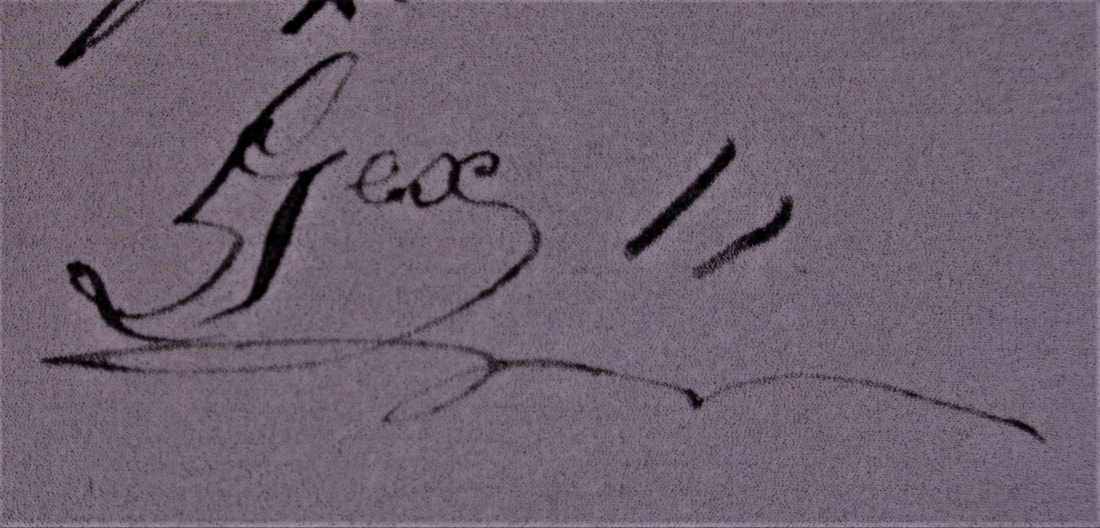

One of the only rural Louisiana stonecutters of the nineteenth century, Lucien Gex led a life far different than his New Orleans counterparts. Between New Orleans and Baton Rouge, the Mississippi River winds through historic landscapes that today are dominated by chemical plants, refineries, plantation interpretive sites, and small towns. These are the River Parishes – St. James, St. John the Baptist, and St. Charles. Historically, they are also known as the German Coast. The cemeteries of the River Parishes are as old as their oldest New Orleans counterpart. They date to late-eighteenth century settlements of Germans and Acadians and memorialize the names of families that still dwell in the area: Waguespack, Aime, Webre, Roman. Moreover, they bear the names of some of the best-known French-associated stonecutters of New Orleans: Florville Foy and Paul Hippolyte Monsseaux, especially. But among the craftsman names inscribed on tombs and tablets of River Parish cemeteries is one name that will not be found in New Orleans: L. GEX. Written only on a handful of headstones, this is the last memorialization in stone of a man who may himself not have a grave marker at all. In this blog post, we will attempt to share what we know (and what we do not know) about Lucien Gex, one of southern Louisiana’s only rural stonecutters. The Country Sculptor The surviving cemetery stonework of Lucien Gex is unusual in several ways. For one, his work was distinctively French influenced. Gex’s acroteria and acroteria-inspired shapes mimic those of Foy, Monsseaux, and other French-extracted stonecutters of mid-nineteenth century southern Louisiana. Secondly, Gex’s work is rare. In our studies of River Parish cemeteries, surviving work with Gex’s signature only amounts to four or five monuments in two different cemeteries. His surviving work ranges from a small sarcophagus tomb in St. James to several limestone headstones in St. Michael’s Cemetery. Unlike some stonecutters like Florville Foy, for whom examples of work range from dozens to hundreds, Gex’s body of work is extraordinarily restricted. Finally, Gex’s work is rural. In the 1840s and 1850s when Gex was active, the vast majority of cemetery stonework was produced in urban centers like New Orleans and to a lesser extent Baton Rouge, Mobile, and other larger towns. It was precisely the nature of this urban-center cemetery craft economy that led to stonework signed by New Orleans cutters appearing in cemeteries from Pensacola, Florida, to Natchitoches, Louisiana, and beyond. For any of these rural communities to have their own cemetery craftsperson would be unusual at best and economically unfeasible at worst. Yet, Lucien Gex was a St. James Parish cemetery stonecutter. New Orleans stonecutters did not have the same relationship with the River Parishes as Gex did, although some straddled two worlds. Stonecutter Prosper Foy (1793-1854) had a stone-carving shop in New Orleans as early as 1807. In addition to the French Quarter shop, he also owned a plantation and approximately 14 enslaved people in St. James Parish. He owned this property until his death in the 1850s. It doesn’t appear as if Prosper Foy interacted with Gex, but he did carve and sign cemetery markers for his community, including the 1827 box tomb of his neighbor Michel Poirrier.[1] Stonecutter Charles Crampon also had an unusual relationship with New Orleans’ rural hinterland. Though he himself was based in New Orleans, Crampon’s signed work is never found in Crescent City cemeteries: it appears as if he served only rural clientele. But, unlike Gex, Crampon’s home base was in the city.

It is curious, then, that within the year Lucien Gex would marry Elizabeth Menny[4], whose father was from New York. Elizabeth herself was a native of St. James Parish, as was her Irish-American mother. Gex and Many were married on April 21, 1849 in the church of St. Michael in Convent.[5] Over the next sixteen years, the couple would be part of the larger St. James community and the slave plantation economy that was critical to the area in the nineteenth century. Saint James Parish in the Nineteenth Century Saint James Parish was driven by the presence of sugar plantations on either side of the Mississippi River.[6] By the time Lucien Gex arrived, many of those plantations were owned by a small number of families who were interrelated by marriage.[7] The Aime, Roman, Webre, and Bourgeois families owned several plantations in St. James Parish, and were simultaneously neighbors and contemporaries of Lucien Gex and his family. Lucien Gex was by no means a sugar planter. He most likely lived in or near the area now known as Convent, a township that included St. Michael’s Church and what is now the Manresa House of Retreats (formerly Jefferson College). In Gex’s time, Convent (or College Point, or St. Michaelstown) was home to a post office, a saw mill, butcher shops, coopers, and other resources to serve the rural community.[8] Gex himself owned at least five slaves in St. James Parish, but does not appear to have been a farmer or planter.[9] Instead, he seems to always have referred to himself as a sculptor or a marble cutter. Part of the Community From 1848 to the late 1860s, Lucien Gex would be bound to the plantation community in all manner of civic events. He and Elizabeth Menny would have at least seven children, five of which would live to adulthood. Members of planter families like Marie Azelina Rodrigue and Antoine and Palmire Webre would become godparents to their children. Gex sold at least one enslaved woman to the Roman family which, along with the Aime family, dominated the sugar plantations on the right bank of the Mississippi River. When Gex signed contracts, bought items at auction, and attended church, members of these families were his primary contacts. In turn, it appears that Gex carved at least some of their headstones when they died. For example, in 1847, Gex produced likely his most notable surviving work: the Classical Revival sarcophagus tomb of Jean Emile Richard in St. James Cemetery. Five years later, Gex attended the probate auction of Emile’s mother, Marguerite Richard Bernard, and purchased two old tables and a cow.[10] In 1853 he carved the limestone tablet on a tomb in St. Michael’s Cemetery for his neighbors, the Boucry family. In the late 1840s, he carved at least one headstone for the Bourgeois family, members of which had been members of his community for years. While it is clear that Gex was familiar with and interacted with this small community in rural St. James Parish, it is less clear how successful a stonecutter he was. It is difficult to understand Gex’s place in the St. James plantation economy. On one hand, it is possible that Gex was in fact much more prolific than what is evidenced today, but examples of his work do not survive. This theory is supported by the fact that cemeteries in St. James and St. John the Baptist Parish have shrunk over the years as levees and flood protection have encroached. It is also possible that Gex’s sculptural work served plantation families more directly: perhaps by carving decorative statuary for homes or gardens, or perhaps by carving funeral markers for private family cemeteries. If this is the case, no evidence is readily available to support it.

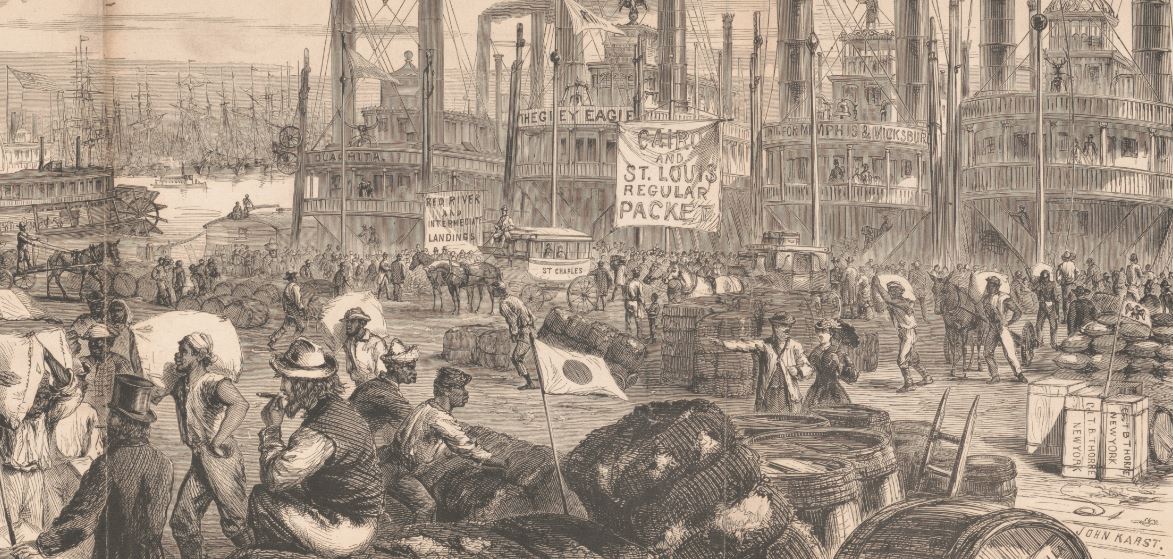

It appears that the anchors that kept Lucien Gex in St. James Parish were cut after the Civil War and the death of his wife. Gex would begin to appear in other towns doing work besides stonecutting. In the late 1860s, he ran small grocery and produce operations in Lockport and Donaldsonville with two partners named Kelly and Mizzi.[14] Finally, Lucien Gex moved to New Orleans around 1869. By 1871 his grocery firm had dissolved and he moved on to a new venture: a wine and liquor store on Conti Street in the French Quarter. Lucien Gex lived above the store, which he owned with his partner Gustave Chagnard. At this time, Lucien Mirtile Gex, son of Lucien Sr., was working for his father’s former partner, Joseph Mizzi. But this would not last: the partnership of Gex and Chagnard dissolved in 1874.[15] The rest of Gex’s life in New Orleans appears to have been spent settling debts and fighting legal battles in both St. James and St. John the Baptist Parish, either with debtors to Gex’s former grocery interests or with concerns of seized or embattled land.[16] Gex died on May 31, 1876 at his home, 197 Treme Street, of heart failure. He was fifty-nine years old.[17] At the time of his death he had five surviving children, including sons Lucien Mirtile and Edward, who managed his funeral. According to probate records, Lucien Gex had less than $500 at the time of his death, and no debts. It is unclear where Lucien Gex was buried after his own death. Unlike his wife, infant children, and brother Edouard, he was not buried in St. Michael’s Cemetery in Convent. He likely was buried in one of the Catholic cemeteries of New Orleans, possibly St. Louis Cemetery No. 2, as it was the closest cemetery to his home. But current survey documentation shows no surviving tablet or headstone to memorialize him. So many of the stonecutters we research at Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC, are clearly men of their time. From Florville Foy to Albert Weiblen, each craftsman is an historic figure with a relevant context, and his work and life usually bear that out. Lucien Gex may in fact be a man for his time and place – specifically antebellum rural Louisiana and the subsequent economic and social shifts of Reconstruction. His migration to the city seems to suggest as much. Yet much like the rural landscape he once occupied, now populated by more industrial and chemical plants than sugarcane fields, the details that make his relevance clear are no longer visible. Instead there are only a handful of small, barely-legible signatures to remind us that Lucien Gex was part of the landscape at all. [1] National Archives and Records Administration, Sixth Census of the United States, 1840, Right Bank of the Mississippi, Saint James, Louisiana, Roll 135, Page 265; National Archives and Records Administration, Seventh Census of the United States, 1850, Eastern District, St. James, Louisiana, Roll M432_239, Page 206A; Patricia Brady, “Florville Foy, F.M.C.,” in Southern Quarterly 31, No. 2 (Winter 1993), 10-11.

[2] St. James Parish Clerk of Court, Marriage of Lucien Gex and Elizabeth Menny, April 21, 1849, Conveyance Book 28, Page 107. [3] St. James Parish Clerk of Court, Sale of Land between Lucien Gex and Henri Baudet, April 28, 1848, Conveyance Book 24, Page 294. [4] Also spelled “Many” in other documentation. [5] St. James Parish Clerk of Court, Marriage of Lucien Gex and Elizabeth Menny, April 21, 1849, Conveyance Book 28, Page 107. [6] Ibrahima Seck, Bouki Fait Gombo: A History of the Slave Community of Habitation Haydel (Whitney Plantation) New Orleans: UNO Press, 2014, 78-80. [7] Roulhac B. Toledano, “Louisiana’s Golden Age: Valcour Aime in St. James Parish,” Louisiana History, Vol. 10, No. 3 (Summer 1969), 211-224. [8] Lillian Bourgeois, Cabanocey: The History, Customs, and Folklore of St. James Parish (Gretna: Pelican Publishing, 1976), 61. [9] United States Census (Slave Schedule), 1860; https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-GB9J-9BFS?cc=3161105&wc=818R-JWL%3A1610422401%2C1610423201%2C1610423301; St. James Parish Clerk of Court, Sale Slave from Lucien Gex to Roman & Choppin, July 20, 1852, Conveyance Book 30, Page 261. [10] St. James Parish Clerk of Court, Succession and Sheriff’s Auction of Marguerite Richard (widow Andre Bernard), February 10, 1853, Conveyance Book 30, Page 419. [11] “St-Jacques,” Le Meschacebe, October 19, 1861, 2. [12] St. James Parish Clerk of Court, Sale of Land from Lucien Gex to Lucien Theriot, March 14, 1863, Conveyance Book 36, Page 147. [13] Archdiocese of Baton Rouge, St. Michael’s Church Sacramental Records, Book 22, Page 11. [14] “Steamer Flicker,” Times-Picayune, June 10, 1868, 2; “Steamer Flicker,” Times Picayune, May 27, 1868, 2; “Steamer New Era,” Times-Picayune, June 29, 1869, 3. [15] New Orleans Republican, November 17, 1874, 2. [16] “St. Jean-Baptiste,” Le Meschacebe, January 6, 1872, 2; Donaldsonville Chief, July 10, 1875, 3; Gex v. Landaiche, St. John the Baptist Parish Court Records, Case 497, April 1871. [17] Louisiana Secretary of State, Death Records, Vol. 66, Page 338.

4 Comments

Edward G Breaux

7/10/2020 12:22:49 pm

Do you know if Lucien Gex carved the St Michael statue at St Michaels in Convent LA?

Reply

Emily Ford

7/14/2020 08:08:22 pm

Hey Mr. Breaux,

Reply

Ed Catterson

5/22/2023 11:48:17 pm

Thank you for the very interesting article. I was able to access it , in that I looked up the name Lucien Gex on the internet. You see for the past 25 years , off and on I have been researching the Gex surname. My grandmother was Ellen (Gex) Catterson, her father Robert Brooking Gex from the Northwest Missouri area near Graham. After going to other family lines, I recently picked back up the Gex research again.

Reply

Emily Ford

6/12/2023 06:10:28 pm

Wow! Thanks so much for sharing this, Ed! Very interesting.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

About the Author:Emily Ford owns and operates Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

- About

-

Restoration

- Services

-

Portfolio

>

- Turning Angel Statue, Natchez, MS

- Ledger Monument, Baton Rouge, LA

- Pyramid Statuary, New Orleans, LA

- Bronze and Granite Monument, Carville, LA

- Box Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Vernacular Concrete Monument, Pensacola, FL

- 1830s Family Tomb, Covington, LA

- 1850s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- 1880s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Headstone and Monument Restorations, Pensacola, FL

- Society Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Education

- Blog

- Contact

|

Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC is a preservation contractor in New Orleans, Louisiana, specializing in historic cemeteries, stone conservation, educational workshops and lectures. Oak and Laurel serves the region of the Southeastern US.

|

QUICK LINKS |

CONNECT |

Proudly powered by Weebly