|

Adapted from Emily Ford, “The Stonecutters and Tomb Builders of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, New Orleans, Louisiana,” Master’s Thesis, Clemson University, 2012. Full text can be found for free here. How is a cemetery preserved? Depending on who you ask, a cemetery is preserved by the involvement of families who have ancestors buried there, by maintenance, by thoughtful landscape management, by using good repair materials. But an historic cemetery is also best preserved by understanding its history. Despite the common adage that cemeteries are “outdoor museums,” they are in no way that static. They are amalgamations – in a very small space, usually – of decades and centuries of intervention, construction, and memory. Understanding the biography of any given cemetery is the key to its preservation. Some layers of a cemetery’s history can be more important than others. In the case of New Orleans cemeteries, the period between roughly 1880 and 1915 represented a crucial turning point in construction, management, and architecture. Today, we examine this period and why it matters. Turning the Corner From the late nineteenth century into the second decade of the twentieth, tomb building in New Orleans shifted from a neighborhood cottage industry to an interconnected network of local tomb builders and national sales agents. The old order of the 1800s – the sexton/stonecutter living in the cemetery using local materials to build vernacular tombs – began to fall away and give rise to the sales agent, the for-profit cemetery operator, and other trappings of the cemetery industry that would boom by mid-century. In short, this period marked a big change in scale. This change was only possible because national trends made it so. New materials were transported on new infrastructure to a new network of cemetery artisans and craftsmen. This was the era of Georgia marble, of expanding railroads, and new types of cement. Nation-wide Changes This period so significant to the cemeteries of New Orleans spans across the national periods of the Gilded Age and the Progressive Era. The late nineteenth century was a period of economic growth and opportunism, and New Orleans was no less effected by this than anyplace else. For the cemeteries, this meant new materials with which to build tombs. New Orleans bricks were traditionally made by dredging clay from either the Mississippi River or from water sources in St. Tammany Parish like Lake Pontchartrain. The clay was cured using rudimentary mechanical means – usually a mule pulling a churning apparatus through clay beds. The clay was then placed into wooden molds, shaped, and fired. But by 1880, technologies like dry-pressing and wire-cut extrusion had arrived in New Orleans. New bricks were mass-produced, harder, sharper, and less porous. Cement technology was also changing. For nearly 200 years, New Orleans tombs were built using hydrated lime produced by burning oyster shells or limestone. By the turn of the century, however, primitive methods of producing Portland cement were reaching the Crescent City. This meant that bricks could be laid faster and higher than before. These new cements could also be mixed with different aggregates formed into molds to create cast concrete. In the early twentieth century, the versatility of cast concrete would be limited to walls and coping facades – however, into the 1920s and 1930s the material would become downright artisanal. Along with new bricks and new cement, turn-of-the-century stonecutters found that granite, which to previously had been extremely difficult to carve with contemporary tools, was newly accessible. Pneumatic tools – chisels, saws, and others – made cutting, carving, and building with granite possible.

This role was in all senses hyper-local. Each cemetery’s sexton lived either directly beside or sometimes even within the cemetery. There were few exceptions to this – for example, in the 1870s, St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 and 2 sexton J.F. Callico did a brief stint as the sexton of the Lafayette Cemeteries, even though he lived downtown. But in most cases, the sexton lived across the street from the cemetery. For St. Vincent de Paul, the Suarez brothers lived around the corner on Urquhart Street. St. Joseph Cemetery sexton Matthias Huber lived across from the cemetery on what is now South Rampart Street. Hugh J. McDonald, stonecutter and sexton of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, lived nearby on Conery Street.

Cooperation in a Time of Epidemic The yellow fever epidemic of 1878 killed more than 4,000 people, approximately 2% of the population of New Orleans at the time. Not since 1853 had the cemeteries been so overtaxed with burials and new construction. But tragedy makes strange bedfellows, and the pressing need for burial space caused many stonecutters to begin to work together in ways not witnessed before. The new materials of the age were put to work as both mentors and apprentices set to work building tombs that were nearly identical to one another, creating near-subdivisions in cemeteries like Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. Among the stonecutters who worked together over the yellow fever epidemic of 1878 were an entire cohort of old and new faces in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. J. Frederick Birchmeier was on the scene with his two apprentices – Gottlieb Huber (son of St. Joseph Cemetery sexton Matthias Huber) and Hugh J. McDonald. Working alongside them were stonecutters even younger than them – namely Henry Alfortish and likely Charles Badger. These folks would take up their mentor’s mantels in the coming years: When Birchmeier passed away in 1890, Hugh J. McDonald carried on his business. McDonald died in 1895, at which point Gottlieb Huber took over the Lafayette Cemetery stonework with Charles Badger and Henry Alfortish as his employees. Charles Badger married Birchmeier’s daughter. Over the coming century, each man would serve as sexton of Lafayette No. 1 until 1945, when the descendants of Henry Alfortish moved to Gretna to continue Alfortish Marble and Granite Company.

The new generation of cemetery craftsmen would go on to work with cast stone, carving tablets with pneumatic tools, building tombs from granite. Later, they would be the innovators of poured-in-place concrete and granite slab. But no one member of this group would be so wholly invested in the new ways than Albert Weiblen. Albert Weiblen (1857-1957) We’ve written Weiblen’s biography elsewhere (check out the blog post here). But, in short, Albert Weiblen was the Renaissance man of the great New Orleans cemetery transition. Starting as a stonecutter for the firm of Kursheedt & Bienvenu, Weiblen struck out on his own in the 1880s. By the turn of the century, he was designing some of the greatest tombs in Metairie Cemetery. Moreover, he was tooling with logistics and breaking all the old rules. Weiblen opened up a marble shop on City Park Avenue along the New Basin Canal and between Cypress Grove and Metairie Cemeteries. From this spot, Weiblen could haul in marble and granite from the Elberton, Georgia quarries that he owned outright. He flooded the market with Georgia marble and “Weiblen gray” granite. Today, Metairie Cemetery bears his mark on every aisle. Landscapes of Yesterday and Today

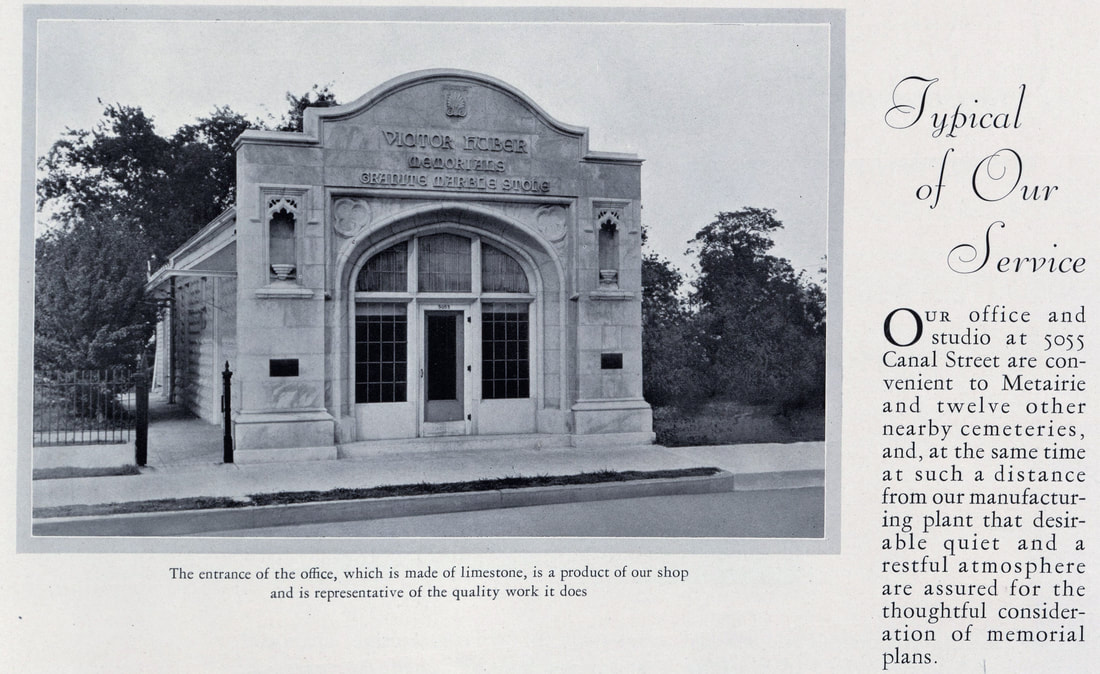

While Albert Weiblen was transforming the Canal Street Cemeteries (alongside folks like Barret and Victor Huber, who would develop Hope Mausoleum there in the 1930s), the Stewart family bought their first cemetery, St. Vincent de Paul Cemeteries 1, 2 and 3, on Louisa Street, around 1904. This purchase began a century-long journey of the family that would end with their ownership of Metairie Cemetery, St. Vincent de Paul, Lake Lawn Park Mausoleum, and others. That journey ended with Stewart Enterprises being one of the largest funereal companies in the world. It merged with Service Corporation International in 2014. The great turn of the century in New Orleans cemeteries created an enormous stock of cemetery architecture that is materially and aesthetically different from all that came before. In this time, coping tombs cropped up in cemeteries like Valence Street and St. Roch, replacing wooden headboards that are all but erased today. In Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, no viewpoint in the entire landscape is free from recollections of the 1878 epidemic. Today, the men that led this transition rest in the cemeteries themselves. The period between 1880 and 1915 created the cemeteries as we know them today. In many ways, the modern interventions of the period erased much of what came before. In an ironic turn, these same interventions are themselves at risk of erasure as the twin threats of neglect and present-day modern intervention spread through the cemetery landscape. But we can know them for what they are and preserve them appropriately. We just need to remember where to look.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

About the Author:Emily Ford owns and operates Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

- About

-

Restoration

- Services

-

Portfolio

>

- Turning Angel Statue, Natchez, MS

- Ledger Monument, Baton Rouge, LA

- Pyramid Statuary, New Orleans, LA

- Bronze and Granite Monument, Carville, LA

- Box Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Vernacular Concrete Monument, Pensacola, FL

- 1830s Family Tomb, Covington, LA

- 1850s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- 1880s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Headstone and Monument Restorations, Pensacola, FL

- Society Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Education

- Blog

- Contact

|

Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC is a preservation contractor in New Orleans, Louisiana, specializing in historic cemeteries, stone conservation, educational workshops and lectures. Oak and Laurel serves the region of the Southeastern US.

|

QUICK LINKS |

CONNECT |

Proudly powered by Weebly