|

One of the only rural Louisiana stonecutters of the nineteenth century, Lucien Gex led a life far different than his New Orleans counterparts. Between New Orleans and Baton Rouge, the Mississippi River winds through historic landscapes that today are dominated by chemical plants, refineries, plantation interpretive sites, and small towns. These are the River Parishes – St. James, St. John the Baptist, and St. Charles. Historically, they are also known as the German Coast.

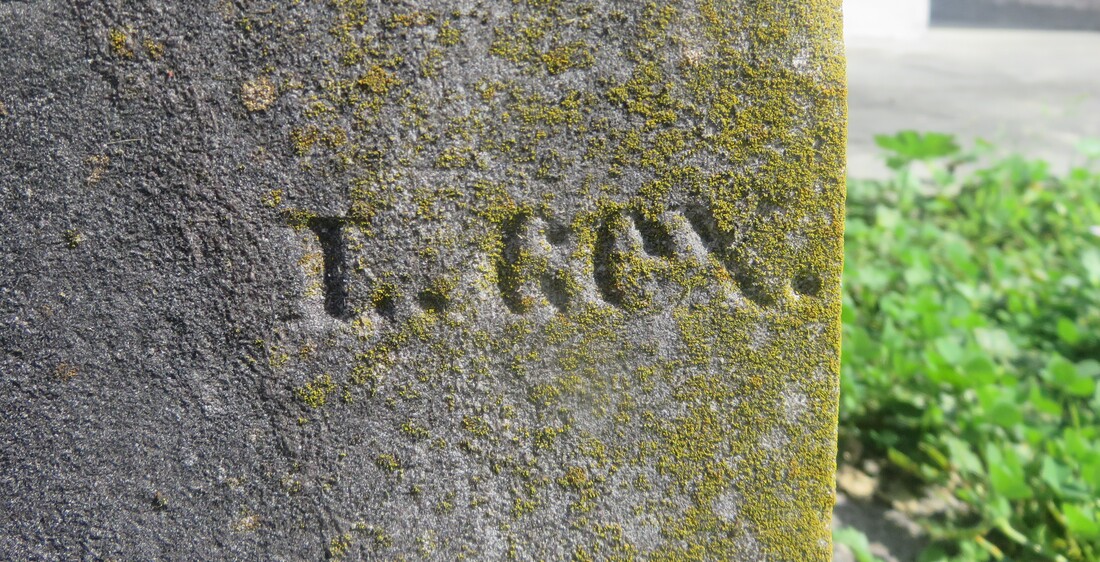

The cemeteries of the River Parishes are as old as their oldest New Orleans counterpart. They date to late-eighteenth century settlements of Germans and Acadians and memorialize the names of families that still dwell in the area: Waguespack, Aime, Webre, Roman. Moreover, they bear the names of some of the best-known French-associated stonecutters of New Orleans: Florville Foy and Paul Hippolyte Monsseaux, especially. But among the craftsman names inscribed on tombs and tablets of River Parish cemeteries is one name that will not be found in New Orleans: L. GEX. Written only on a handful of headstones, this is the last memorialization in stone of a man who may himself not have a grave marker at all. In this blog post, we will attempt to share what we know (and what we do not know) about Lucien Gex, one of southern Louisiana’s only rural stonecutters.

4 Comments

Adapted from Emily Ford, “The Stonecutters and Tomb Builders of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, New Orleans, Louisiana,” Master’s Thesis, Clemson University, 2012. Full text can be found for free here. How is a cemetery preserved?

Depending on who you ask, a cemetery is preserved by the involvement of families who have ancestors buried there, by maintenance, by thoughtful landscape management, by using good repair materials. But an historic cemetery is also best preserved by understanding its history. Despite the common adage that cemeteries are “outdoor museums,” they are in no way that static. They are amalgamations – in a very small space, usually – of decades and centuries of intervention, construction, and memory. Understanding the biography of any given cemetery is the key to its preservation. Some layers of a cemetery’s history can be more important than others. In the case of New Orleans cemeteries, the period between roughly 1880 and 1915 represented a crucial turning point in construction, management, and architecture. Today, we examine this period and why it matters. As the weather cools down, cemetery managers and community groups look to living history performances to inspire support and interest in their historic landscapes. It’s that time of year again! The weather is cooling down, the pumpkins are in their patches, and our minds turn toward the ethereal, mysterious landscapes of cemeteries.

It’s also the time of year when a lot of preservation, heritage, and municipal groups hold annual cemetery fundraising events in the form of living history tours. Events like these connect the public with historic cemeteries in a unique way – visitors walk through the cemetery, often at night or twilight, and meet the “residents” of the cemetery. Through drama (and sometimes music), visitors can connect with the importance of the cemetery to local history and culture. Living history tours are also a whole lot of fun! Wherever you are in the South this year, there is a living history event in a cemetery near you. It might be Natchez City Cemetery’s annual “Angels on the Bluff” tour, a large-scale event that sells out every year, as does Oakland Cemetery’s “Spirits of Oakland” program in Atlanta. But it also might be a smaller event hosted by a local historical society. Check out the listings below to plan your cemetery visit – it makes a great date night or family outing. How were some of New Orleans' most beautiful tombs designed, and why? The architecture of New Orleans cemeteries is as diverse and varied as the neighborhoods in which the cemeteries are set. On one end of town, St. Vincent de Paul Cemetery grew from a peaceful field in the 1830s into a florid, tightly-packed garden cemetery full of Spanish and Italian inscriptions by the 1860s. Far uptown, the Americans built Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 from a below-ground graveyard into a little city of stone tombs in the same period. Between the two of them, the French-Creole cemeteries St. Louis No. 1 housed several generations of architecture within its walls decades before either Lafayette No. 1 nor St. Vincent de Paul were even conceived of.[1]

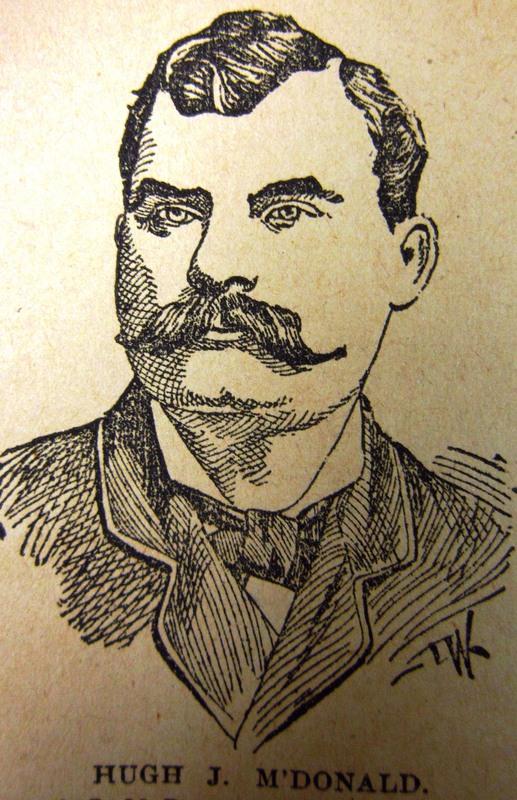

Each tomb’s design in each cemetery is an adaptation of myriad influences, determined through the eye and imagination of mostly vernacular builders. Yet as is the case in all cemeteries, the appearance of the present is determined by what came before. In this blog post, we examine how a single influence gained a dual life in the form of the New Orleans sarcophagus tomb. The life and times of a New Orleans cemetery caretaker. Adapted from Emily Ford, “The Stonecutters and Tomb Builders of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, New Orleans, Louisiana,” Master’s Thesis, Clemson University, 2013. New Orleans cemeteries are centers of its heritage, not only as the final resting place for great historical figures, but also as places where historic craftwork endures in brick and stone. Within the avenues and aisles of the Saint Louis Cemeteries, Lafayette Cemeteries, St. Roch, St. Vincent de Paul, and others, there are hundreds of stonecutters, tomb builders, and vernacular architects for whom, it seems, only a carved signature remains. In Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, for example, nearly two dozen tombs are signed by one such craftsman: H.J. McDonald.[1]

Hugh Joseph McDonald (1848 – 1895) was a stonecutter and tomb builder who spent most of his life within blocks of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1. He was a Civil War veteran, a state representative, local politician, and skilled craftsman. He apprenticed with stonecutters and tomb builders who carried on a long tradition of stewardship to New Orleans cemeteries and, in turn, he mentored those who took his place. He was active during a time of great technological, stylistic, and material changes to the crafts of masonry and monument carving. As an artisan and as a member of his community, he earned his name, written in stone, among the tombs of New Orleans. Lightning strikes are a lot less rare than you would think - especially in Louisiana. There are few things more effective than forces of nature to remind us how small and vulnerable we can be. In summertime, we remember how much heat and storms can up-end our lives and, in turn, we nurture a healthy respect for wind, water, and sun. But even among these elements, lightning holds a special kind of terror and fascination. It can come seemingly from nowhere, striking indiscriminately, and cut lives and fortunes short in an instant.

Today, the chance of being struck by lightning in one’s lifetime are approximately one in 15,300, with an average of 27 people killed by lightning per year in the United States. Over a century ago, in 1858, 59 people were killed by lightning in the US; in 1859, 77.[1] In 1897, 123 people were killed by lightning in the month of July alone.[2] Over the nineteenth and twentieth centuries (and today), many of these deaths took place in Louisiana, which holds claim as the second most lightning-prone state in the union. (Florida is the first.) In this post, we examine the relationship between humans, cemeteries, and lightning. From scientific discovery to struggles for safety, from tragedy to cemetery artwork, lightning has inspired fascination and fear for as long as humans have been stricken by it. How one of New Orleans best-known cemetery stonecutters chose his flower symbols. Iconography is a favorite interest of cemetery researchers and visitors alike. Its symbolic images can be religious (Cohenim hands and water pitchers in Jewish iconography, for example), fraternal (inverted pentagrams and all-seeing eyes, anyone?), occupational, or, in modern times, even outrightly representative of the interests of the deceased.

The symbolism of flowers and plants has a special place in the cemetery landscape. The appearance of a flower offers its own particular aesthetic, while suggesting a larger theme: loyalty, faith, or a life cut short, for example. The origin and popularity of floral symbolism has roots in ancient Greece and flourished in the nineteenth century. New Orleans stonecutters utilized flowers prolifically during this period. Craftsmen from Paul Hyppolyte Monsseaux to Joseph Callico to Albert Weiblen included them in their tablets. But one stonecutter’s use of floral iconography stands out even among his contemporaries. The work of Florville Foy, whose work spanned from the 1840s to the turn of the twentieth century, can be distinguished for its floral work. For this researcher, the appearance of a pansy on a tablet almost guarantees a Florville Foy signature. In this post, we examine Florville’s flowers. Kitsch decor, mid-century modern designs, and complex sales schemes... Community mausoleums – multi-vault, indoor structures that house dozens or hundreds of burials – are ubiquitous in the American cemetery landscape. Many that were constructed between the early 1960s and today remain in regular use, maintained by their owners and cherished by their stakeholders. Some have not fared so well. In this series, we examine the two periods of community mausoleum construction in the United States. In this part, we examine their mid-twentieth century popularity from approximately 1950 to 1980. In both parts, we will examine New Orleans’ role in the community mausoleum movement. (You can find Part One here.)

By 1950, the concept of the community mausoleum was forty years old. But the American public itself had seen several generations, a Great Depression, and two World Wars go by. In a way, the original allure of the community mausoleum had become part of American culture itself – the advertising had worked. A culture that forty years previous had held funerals in the home and generally eschewed embalming now understood the funeral home to be part of “tradition” and embalming to be essential to sanitation. But the world had also changed. The gargantuan technological leaps made to fight World War II had come home in the form of stronger concrete, bigger buildings, and an age of unparalleled American prosperity. Where before the community mausoleum was marketed as, in part, affordable, the appeal of affordability was no longer as necessary. The public wanted a new modernity to separate from the modernity understood by their grandparents. And they wanted it to be maintenance free, clean, and without the cobwebs of yesteryear. The new, midcentury modern community mausoleums would deliver. As discussed in Part One, New Orleans cemeteries were overwhelmingly uninvolved with the early twentieth century community mausoleum. With the notable exception of Hope Mausoleum, none were built in the New Orleans area. The midcentury mausoleum would be much more at home within the Crescent City, with more than a dozen constructed. The influx of community mausoleums was timely in that it coincided with shifts in cemetery management as a whole. Or, how to get rich in cemetery sales without really trying. Community mausoleums – multi-vault, mostly indoor structures that house dozens or hundreds of burials – are ubiquitous in the American cemetery landscape. Today, many that have survived are historic structures. But in their day, they were controversial, revolutionary, modern, and exploitative. In this series, we examine the two periods of community mausoleum construction in the United States, beginning with the 1907-1940 wave of popularity, and revisiting the subject in their mid-twentieth century renaissance. In both parts, we will examine New Orleans’ role in the community mausoleum movement.

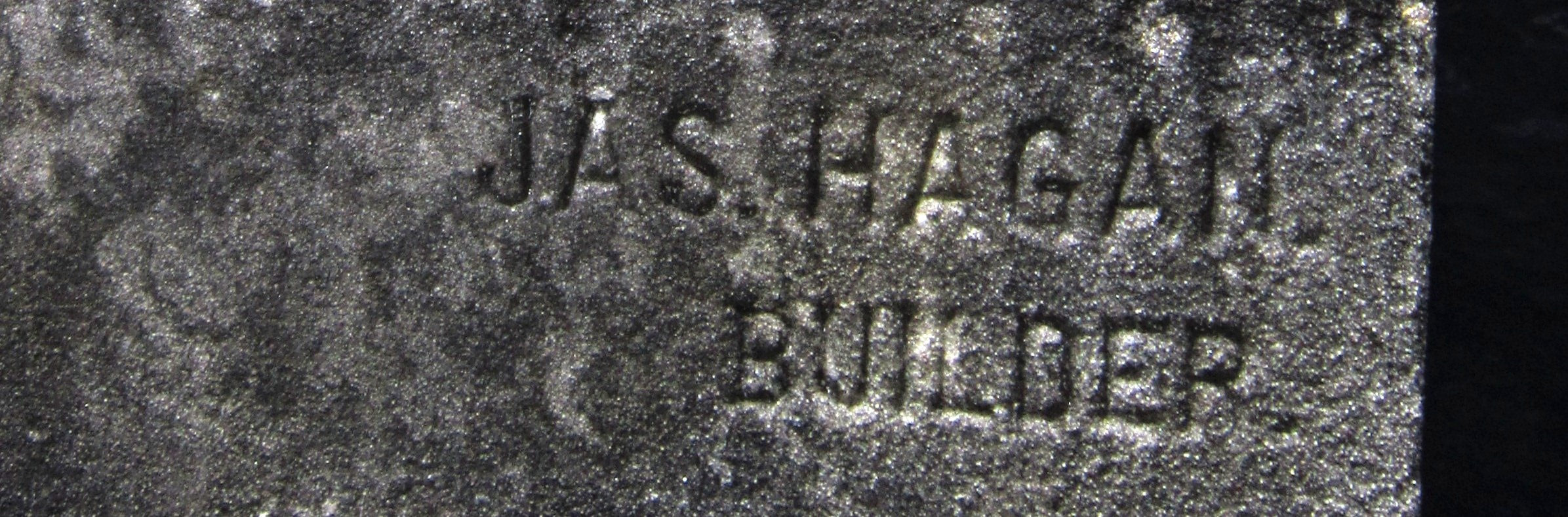

In their time, they were exalted as sanitary, “better way,” a “civilized” mode of burial, while their opponents in the cemetery and monument industries called them “mud houses,” “menaces,” and even “tenement vaults.[1]” They were Neoclassical, Art Deco, Gothic Revival, and even chimeras of architectural design. They were the objects of sales speculation as well as sources of affordability in American cemeteries. They were community mausoleums, and hundreds if not thousands of them survive in the American cemetery landscape today. Beginning in 1907 in Ganges, Ohio and ending in Atlanta, Georgia in 1943, the community mausoleum movement of the early twentieth century embodied changes in the funeral industry, advertising, economics, and the way Americans understood death itself. In New Orleans, only one cemetery can lay claim to part of this movement. Hope Mausoleum on Canal Street is the Crescent City’s only answer to the early community mausoleum, although its founders may have disputed that label. Yet, like other community mausoleums, Hope Mausoleum offered the public a novel kind of cemetery, one that it may not have even known it wanted. Irish-born Hagan was a state senator, a stonecutter, a real estate developer, and a dock commissioner in his long life, and Lafayette Cemetery No. 1 was deeply shaped by his work. Along the main aisle of Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, a pink granite tomb stands out from its lime-washed, marble-clad neighbors. Surrounded by a cast-iron fence, the tomb of James Hagan and John Henderson is often noted as the last resting place of a stonecutter whose work is prominent elsewhere in the cemetery. Yet this note, and the carved name of James Hagan, is only one small detail in the larger story of James Hagan’s life. James Hagan was not only a stonecutter but a real-estate dealer, state senator, community leader, and politician. He lived and worked in New Orleans not only in a time of great social change but a period of high craftwork and architecture in the city’s cemeteries. Among his signed works are some of the most ornate in Lafayette Cemetery No. 1, all marked by detailed stonework and expensive marble cladding.[1] Sources suggest that James Hagan built the pink granite tomb not for himself but for his first wife, Mary Henderson, after her death in 1872. Hagan married Mary Henderson in New Orleans shortly after he immigrated from County Armagh or County Antrim, Ireland, in approximately 1852.[2] James Hagan and his brothers John, Peter, and Patrick, as well as their mother, all fled Ireland in the 1850s after famine likely forced them to emigrate. In the Fourth District of New Orleans, formerly the New Orleans suburb of Lafayette, the Hagans joined thousands of other Irish who had formed a community along the banks of the Mississippi River in the neighborhood now known as Irish Channel.

|

About the Author:Emily Ford owns and operates Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC. Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|

- About

-

Restoration

- Services

-

Portfolio

>

- Turning Angel Statue, Natchez, MS

- Ledger Monument, Baton Rouge, LA

- Pyramid Statuary, New Orleans, LA

- Bronze and Granite Monument, Carville, LA

- Box Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Vernacular Concrete Monument, Pensacola, FL

- 1830s Family Tomb, Covington, LA

- 1850s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- 1880s Family Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Headstone and Monument Restorations, Pensacola, FL

- Society Tomb, New Orleans, LA

- Education

- Blog

- Contact

|

Oak and Laurel Cemetery Preservation, LLC is a preservation contractor in New Orleans, Louisiana, specializing in historic cemeteries, stone conservation, educational workshops and lectures. Oak and Laurel serves the region of the Southeastern US.

|

QUICK LINKS |

CONNECT |

Proudly powered by Weebly